Mr. Israel

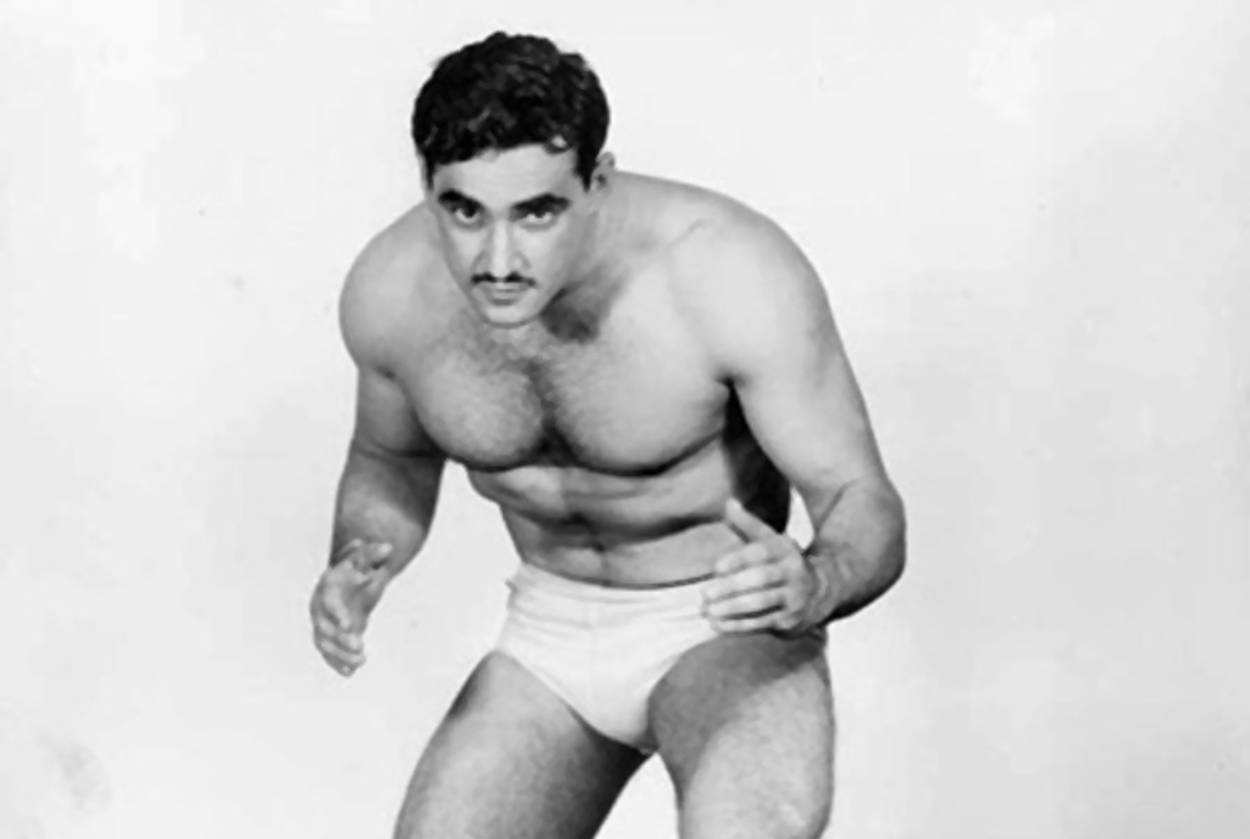

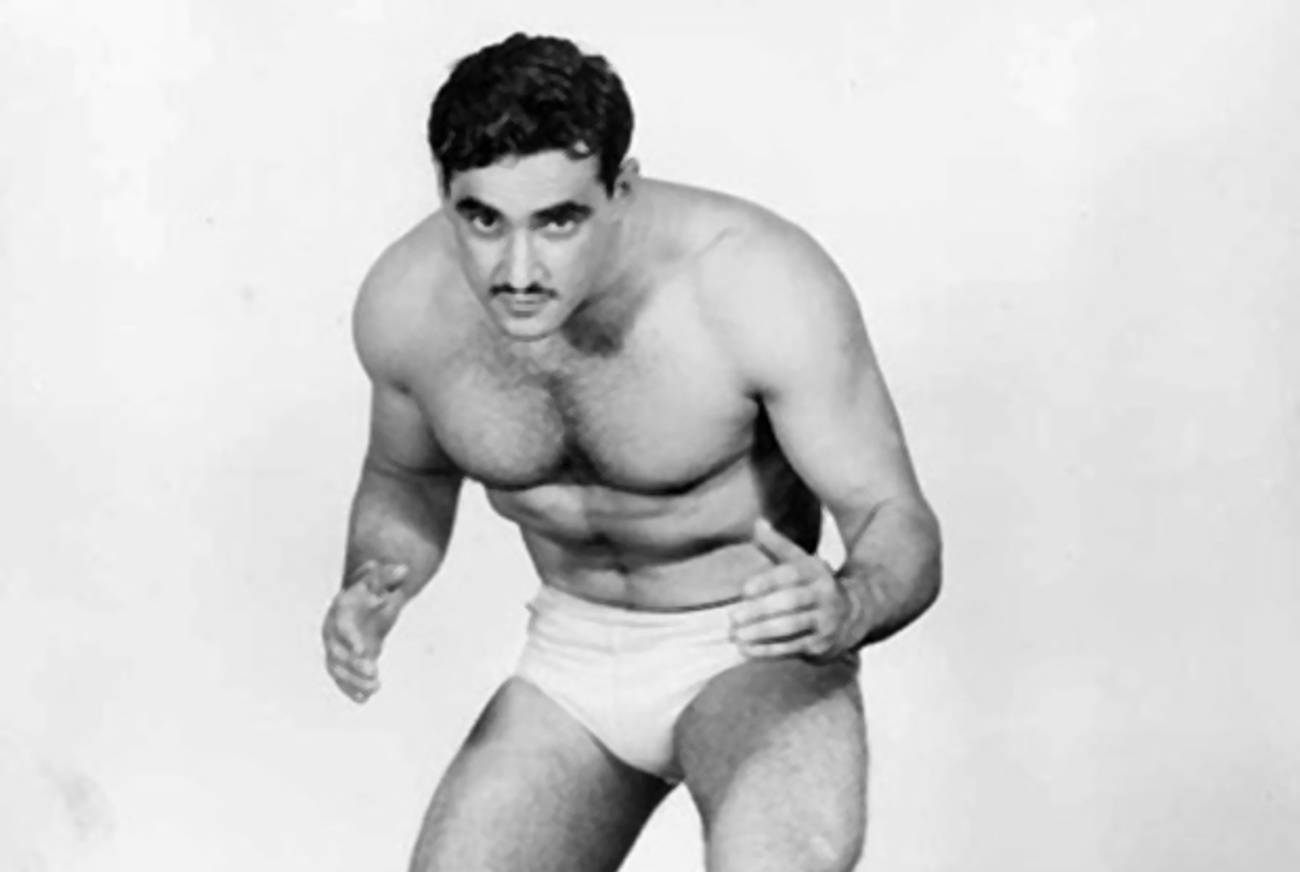

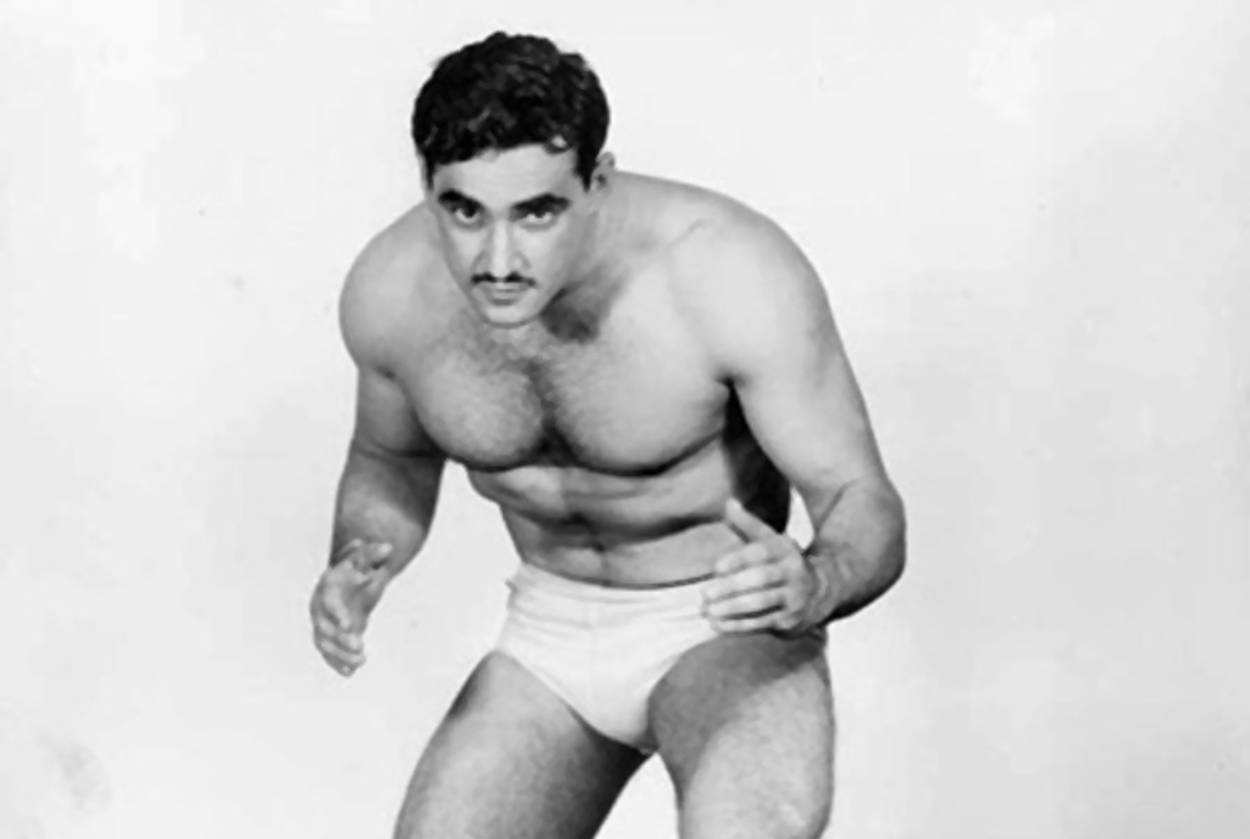

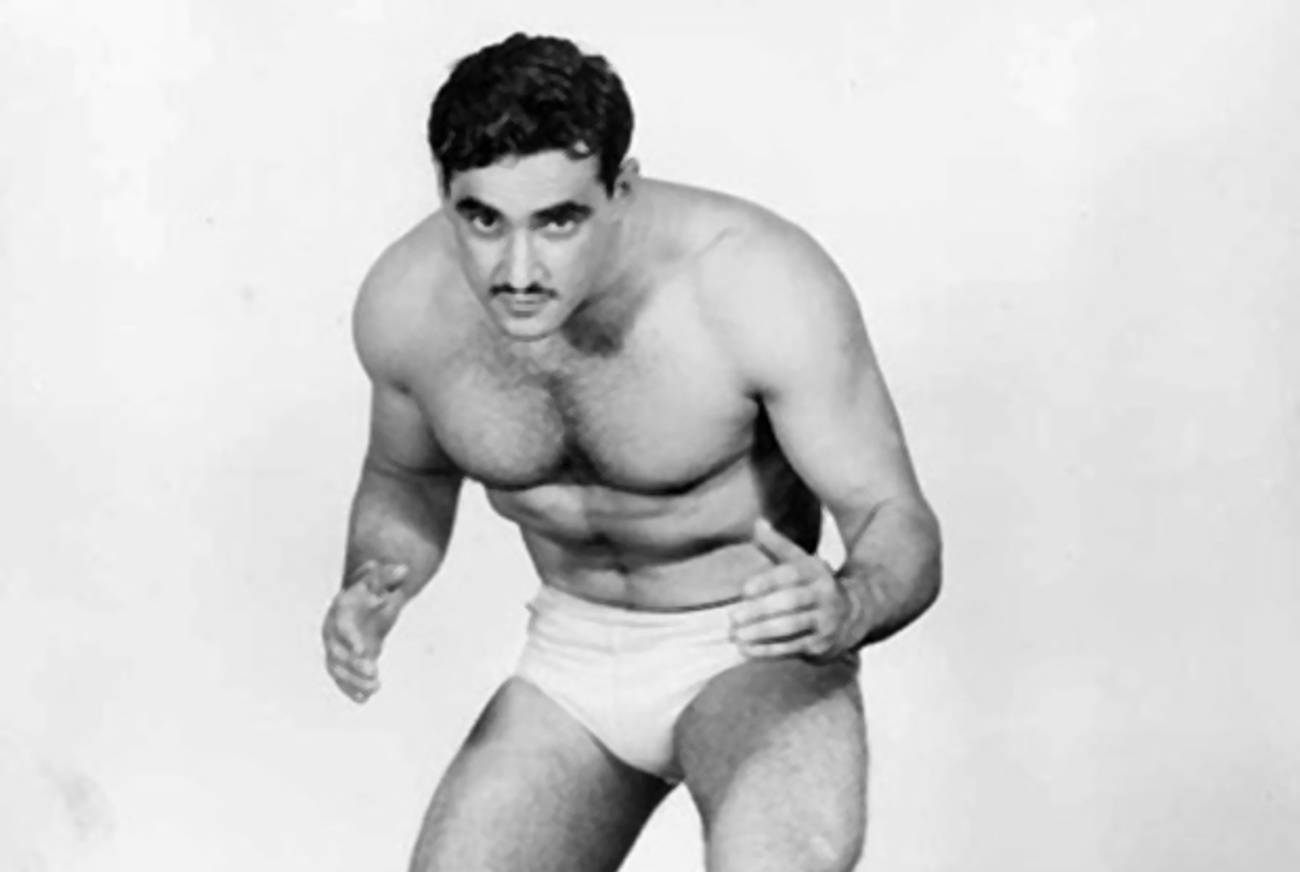

Rafael Halperin—who died last month—was an ordained rabbi, an ambitious businessman, and a middling politician. He was also a professional wrestler.

Rabbi Rafael Halperin, one of the world’s most intriguing rabbinical figures—and surely the only one to have worn a Speedo and grappled with the world’s toughest wrestlers—died last month at the age of 87. He led a terribly unusual life. The Vienna-born strongman was a student of the famed rabbi known as Chazon Ish, an entrepreneur extraordinaire, and an undying defender of the Sabbath. He also caused a number of riots.

Born in Vienna in 1924, Halperin moved with his family to Palestine in the wake of fear produced by the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933. They settled in the religious neighborhood of Bnai Brak, where Halperin’s father would eventually found the ultra-Orthodox Zikhron Meir quarter. Halperin studied in a local yeshiva, but after a few years, he showed interest in more than the Gemara. Attracted by the new physical culture of the Yishuv, Halperin began a regimen of exercise and weightlifting. His parents were furious about it, and his yeshiva buddies thought it was strange. But Halperin approached his rabbi, Avrom Yeshaye Karelitz (better known as the Chazon Ish), the don of the Litvish ultra-Orthodox sect, for approval. Karelitz was known for having engaged in some secular studies of his own, notably the natural sciences, and he told Halperin to carry on pumping iron.

Halperin soon became obsessed with body building, and in 1948, he left Palestine for the United States to study physical culture. Upon his return to what was then Israel, he opened a gym called “Heroes of Israel.” This led to a complaint in the newspaper Davar, which asked that if Halperin was such a “Hero of Israel,” why had he spent the War of Independence in America? In a letter to the editor, Halperin responded that he was, in fact, ready to fight as war broke out in 1948, but had received special permission from the Israeli army to travel to the United States. In the wake of these accusations, he quickly changed the name of his gym to “The Samson Institute.”

Questions of heroism notwithstanding, Halperin organized the first Mr. Israel contest in 1950, and one reporter called the show “a symphony of muscles.” Halperin won the contest, but instead of focusing on the issue that the winner of the event was also its organizer, the Israeli press made much hay from the fact that the winner was a yeshiva-bokher from Bnai Brak. In the eyes of the press, this was proof positive that the new state was creating supermen out of nebbishy, peyes-wearing Clark Kents.

In the early 1950s, apparently at the behest of an American wrestling promoter who was visiting Israel, Halperin entered the professional wrestling world and began to travel to Europe and the United States to perform. He never lost touch with his religious roots. After returning triumphant from a tour in the United States in 1955, Halperin went straight to shul in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea Shearim, where, as he walked down the street carrying his tallis bag, hundreds of ultra-Orthodox kids followed him joyfully shouting, “It’s Samson the Second!”

But Halperin’s strength wasn’t only a feature of his body. The first inkling of a giant entrepreneurial spirit came to light when he turned his gym into the first chain of health clubs in Israel. He called the men’s version “The Samson Institute” and the women’s “The Venus Salon.” He also briefly served as a personal trainer to the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, traveling back and forth from Eilat to Adis Ababa.

In the United States, Halperin was part of a stable of popular Jewish wrestlers promoted by the Warsaw-born wrestling impresario Jack Pfefer. Among them were Blimp Levy, Abie “The Jewish Tarzan” Coleman, Max Krauser, Sammy Stein, and Herby Freeman, among other Yiddish-speaking grapplers. Jewish fans relished the chance to see these Hebrew behemoths compete in the ring. And while it’s well known that wrestling results were often predetermined, Halperin refused to throw matches. Even grizzled American sports writers, like the New York Daily Mirror columnist Dan Parker, were amazed by Halperin’s tenacity.

But in Israel, Halperin battled heavily with the police. He was arrested a number of times in relation to improprieties in the way he ran his businesses. In 1962, he was arrested after a partner alleged that he stole 50,000 Israeli Pounds from the coffers of “New York,” a restaurant Halperin owned on Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff Street. He was also investigated for failing to declare the large number of goods he was bringing into Israel after his trips abroad. In spite of these obstacles, Halperin continued to open restaurants and hotels. In 1965, he ran for mayor of Tel Aviv and lost. His bread and butter remained wrestling—but even that couldn’t keep him out of trouble.

In 1966, Halperin organized a wrestling bonanza in Bloomfield Stadium in Ramat Gan. After the the final match, Halperin entered the ring and addressed the crowd. As he spoke, he was jumped by the angry loser of the main event, a man known as Fuad the Terrible, King of the Arabs from Nazareth. Fuad the Terrible’s real name was Alexander Deligorgos, and he was actually an Armenian from Haifa, not an Arab from Nazareth, but, to the shock of the audience, he began to choke Halperin and slam him to the mat.

Though this gimmick had apparently been planned by Halperin and Fuad the Terrible beforehand, the two had neglected to inform the police, who didn’t know what was happening and rushed the ring to break the wrestlers apart. Convinced that Deligorgos was an Arab attacking a Jew, the audience broke down barricades and tried to attack him. A small riot ensued, and many police were injured trying to protect Fuad the Terrible, who was nearly lynched by the crowd. As a result, Halperin had a hard time finding facilities willing to host his wrestling extravaganzas. The police claimed Halperin was a provocateur and refused to provide security for his matches.

As wrestling wore him down, Halperin began to focus on his many businesses. In addition to his gyms, hotels, and restaurants, he opened the first automat in Israel, on Ben Yehuda Street in Tel Aviv, and he also launched Israel’s first automated car wash. He founded a sports-oriented, “Samson” summer camp for kids. Halperin was a gregarious type and, in spite of his occasional troubles with the authorities, an excellent businessman.

Although he was never typical of any particular strain of Judaism, Halperin always remained religious, and in the 1970s, he returned to yeshiva to earn his rabbinical ordination. In 1981, he founded a political party—and called it Otzma, or strength—and ran for Knesset. More suited to business than politics, Halperin would eventually open the most successful optical chain in Israel: Optika Halperin. Part of Halperin’s profits went to charity, and the chain’s low prices, his ads touted, “smashed the monopoly” of Israeli opticians, forcing them to reduce their prices as well. With the profits from his chain of optical stores, Halperin began to invest in the business he felt was most profitable: the Sabbath.

In the decade following 2000, Halperin funded the development of a credit card that would not function on the Sabbath. He also paid for the installation of Sabbath sirens throughout Israel that alert citizens to the start and end of the weekly day of rest. In 2005, in a political coup, he attracted thousands of Israelis to Tel Aviv’s Nokia Stadium to declare their support of the Sabbath and to encourage storekeepers to close on Saturdays.

But Halperin’s last great business venture was perhaps his happiest. Last year, he opened “Zisalek,” the first glatt kosher ice cream shop in the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood Mea Shearim and the only ice cream shop in Israel with separate lines for men and women. The shop was such a hit that its opening nearly caused a riot. Halperin claimed to be shocked at Zisalek’s popularity. But a riot? He was used to that.

Eddy Portnoy, a contributing editor for Tablet Magazine, is the Academic Advisor and Exhibitions Curator at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is also the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press.

Eddy Portnoy is academic adviser and director of exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, as well as the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford University Press 2017).