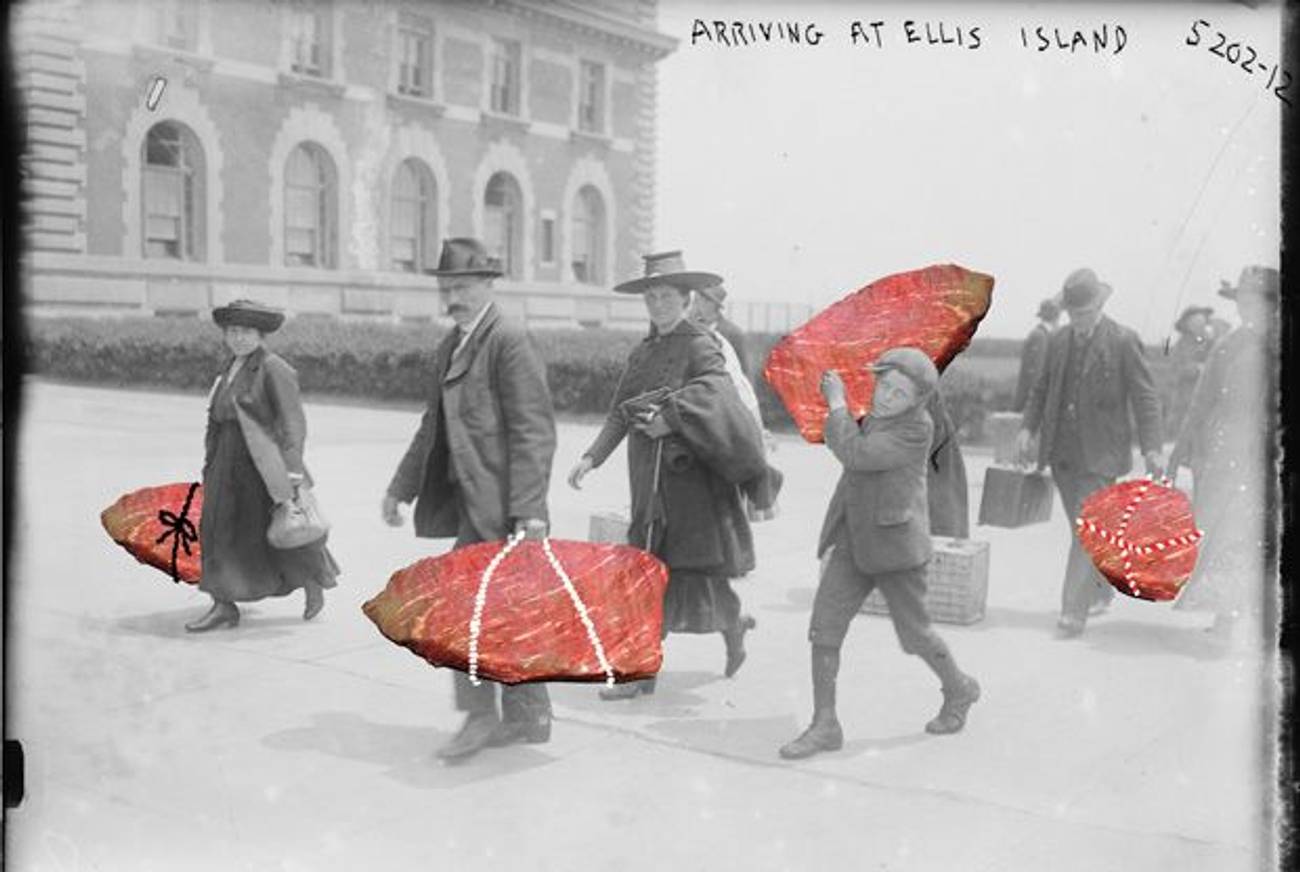

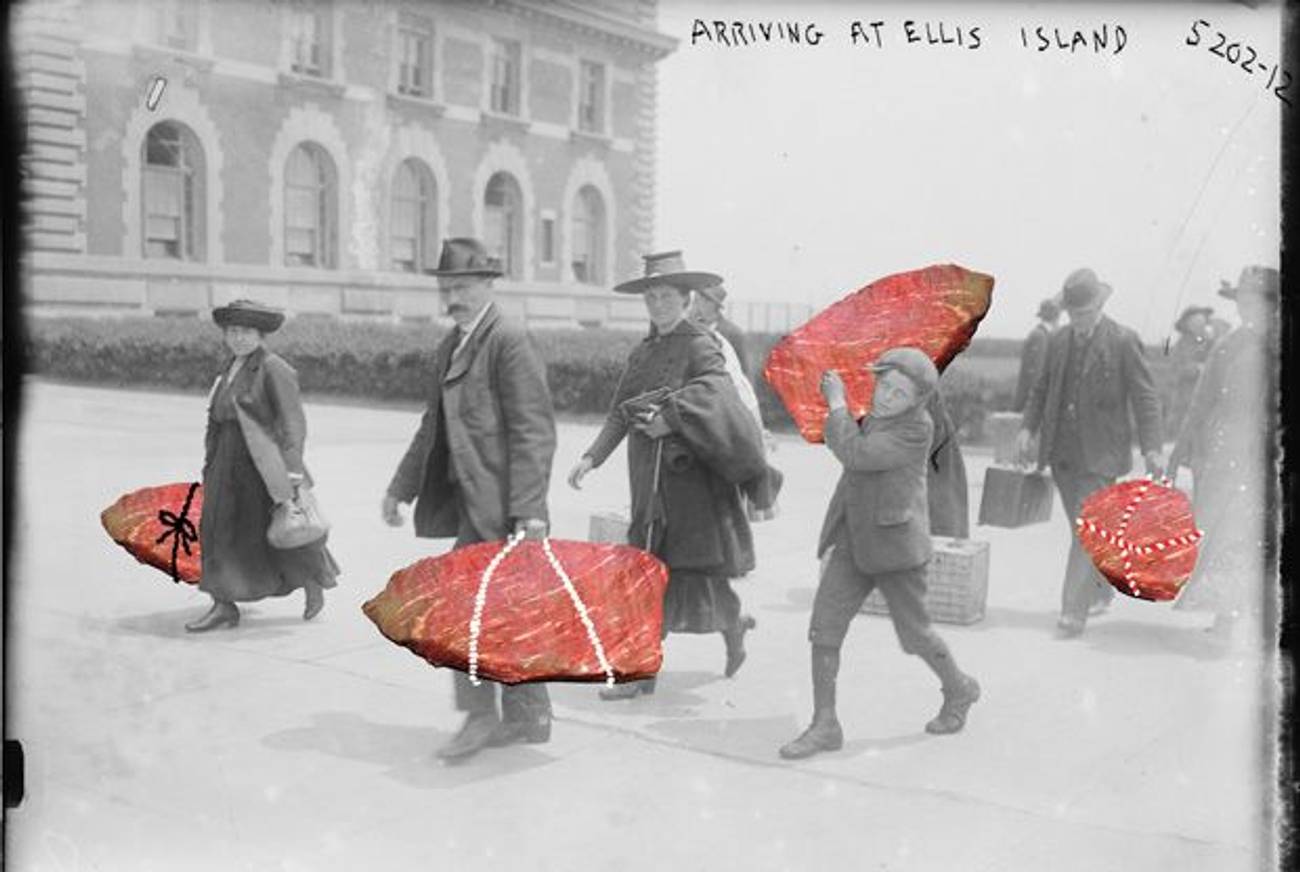

Love Story

Some food will improve your meal; brisket improves your life. In time for the holidays, a book looks at the most beloved of Jewish delicacies.

A buttery, rich madeleine you could understand. So French, so delicate, so, well—so Proustian: “Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy?” But why does a flaccid four-pound, gray-brown piece of beef, shaped roughly like the state of Tennessee, inspire Proustian prose, evoke the deepest pleasure, create indelible memories? I didn’t even know what a brisket was until I was about 25 years old. My mother never made brisket (she was Swedish, a Lutheran lover of lutefisk), but when I put the first voluptuous piece into my mouth, fork-tender, adrift in a rich, sweet onion gravy, accompanied by supernal mashed potatoes and roasted carrots, well—you had me at brisket. (Full disclosure: My father, Mannie, was Jewish, so clearly I have a strong brisket gene.)

Now when I hear that a friend is cooking a brisket for dinner, I get choked up. A brisket? For me? No, it’s too much. You don’t need to do that. We’ll order Chinese. One of my closest friends revealed the secret ingredient in her family’s brisket recipe, and I started to cry. That’s the moment I realized that I needed to get to the bottom of why so many of us have such a strong emotional attachment to this blah cut of beef that doesn’t sit on a steer anywhere near the sexy sirloin or the fancy filet mignon. Is it because even a pretty bad cook can turn a brisket into a pretty decent dish? Does brisket just scream “happy intact family,” even when it’s not your own family? Is it because while we have lost mother tongues, changed our last names, and moved all over the world, we have somehow managed not to lose our recipes for brisket—recipes that have been handed down and copied and emailed and tweeted? (Whose heart wouldn’t melt a little hearing about Aunt Irene’s New England brisket recipe with sherry and mushrooms, which was passed down to her niece Alice, who gave it to her friend Ellen, who shared it with her nephew John, who let his girlfriend—who had never even eaten a brisket—copy it for her mother so she could help her cook it?)

But our passion for brisket goes beyond the recipe or the result. I wondered if there is something to the fact that brisket is just so unpretentious. It has no airs. It has a pretty unimpressive provenance. It did come over early from Europe but is one of a very few not to claim that it came over on the Mayflower. Nor was barbecued brisket born with a silver spoon in its mouth. When the breast of a steer was first slow smoked in the hinterlands of South America and/or the Caribbean, it was by people more likely to be called “natives” than “chefs.” Or could it be that for years, brisket was so affordable you could serve your whole family, invite the neighbors, set an extra place for the rabbi and his wife, and still have leftovers for a week?

While all these things are true and contribute to its lasting resonance, I believe the real reason for brisket’s powerful allure is even simpler. Brisket will be what you want it to be. And that is more than you can say about your teenager, your hair, your Labradoodle, or most members of Congress. On an emotional level, you can celebrate with it, mourn with it, diet with it, defrost with it, court with it, make a friend with it. Come to think of it, there are very few brisket recipes that do not have the word love somewhere in their head notes or descriptions. On a cooking level, it’s a perfect culinary blank canvas, adept at adapting to everything you rub on or throw in, from garlic salt to Liquid Smoke to miso to gingersnaps to huge gulps of Dr Pepper. Joan Nathan rightly calls brisket the Zelig of meats.

During an entire year of brisketeering (I’ll confess to obsession), I cooked with and interviewed some of the country’s top chefs, cookbook writers, pit masters, home cooks, food historians, butchers, and ranchers. I researched the subject hungrily, in hundreds of cookbooks, history books, culinary memoirs, and tomato sauce-stained archival recipe books. I traveled from Maine to Kansas City to Baltimore to Brooklyn to eat brisket and, because I love my boyfriend almost as much as I love brisket, once brought two pounds of still-warm leftovers home from Boston on Jet Blue in the overhead.

The result? Now brisket has its own book. I carefully evaluated the merits of every brisket recipe as well as the intentions of every brisket maker. My method? High hopes. Higher standards. Tender meat and tough love.

These recipes have won competitions, won hearts, made us smile at their utter simplicity, surprised us with their ingenuity, dazzled us with their flavor, touched us with their devotion to not changing a single thing. (One favorite, a braised brisket recipe from Nach Waxman, a historian and founder of New York’s Kitchen Arts & Letters, is included here.) It is clear—and wonderful—that there are many different roads to brisket bliss. To quote the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Mark Strand: “I raise my fork and I eat.”