Oh, Sylvia

Pioneering feminist comics artist Nicole Hollander has drawn her big-haired, big-nosed heroine for 30 years

I have loved Sylvia, the acerbic comic-strip heroine, since I was in college. Back then, when I was discovering feminism and the fact that it was compatible with humor, she was at the height of her influence—a deadpan, big-nosed, big-haired, fabulously earringed commentator on human foibles who watched a lot of TV, drank a lot of coffee, and liked cats and baths. I could relate.

Sylvia’s creator, Nicole Hollander, wrote a comic strip that ran in some 80 newspapers, including big ones like the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, The Detroit News, and Hollander’s hometown paper, the Chicago Sun-Times. (It moved to the Tribune a year or two later.) But earlier this year, Sylvia was pink-slipped by the Trib; these days the strip runs in only 30 or so newspapers, as well as online. It’s more proof that newspapers are screwed. Maybe you’ve heard.

So, thank heavens for the new collection The Sylvia Chronicles: 30 Years of Graphic Misbehavior From Reagan to Obama. “For thirty years, long before Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert, my friend Nicole Hollander has been one of our nation’s leading satirists,” Jules Feiffer writes in a foreword. “That means that she is in the business of telling the truth and making it funny. She is right about almost everything. And because she is right, and she is funny, she has no power whatsoever.”

Nicole Hollander doesn’t look powerless. At 71, she radiates charisma. She’s tiny, with a big voice, gleaming, spiky-chic white hair, fabulous earrings, and snazzy little round glasses. She looks like an artist and an intellectual. I guess she is powerless. “I created Sylvia to say what I couldn’t,” she told me.

Last week, I talked to her about her life and Sylvia’s.

Your work feels very Jewish to me, even if the Judaism isn’t explicit.

My father was an atheist. He encouraged me to eat on Yom Kippur. He might have even handed me a candy bar and suggested I eat it outside in full view of everybody. What he believed in was unions. Both my parents believed it was important to be part of the community, to give to your community. That’s a Jewish value. I don’t feel art is selfish, exactly, but I wanted to be part of something more. When I found the feminist movement, it gave me direction. I could take my drawing and my humor and my politics and put them all in one place.

You grew up in Chicago—your father was a carpenter and your mother was a hospital administrator. Was Sylvia based on people you knew?

Sylvia is modeled after my mother and her two friends Esther and Olga. I loved to listen to their conversations—all the jokes and irreverence and backbiting. [“They’d sit around a table and smoke and linger over coffee and coffee cake (does anyone eat coffee cake now?)” Hollander writes in The Sylvia Chronicles. “They had their coffee with half-and-half. Low-fat milk was not even a bad dream back then; but on the other hand there was no cappuccino, so it wasn’t paradise.”]

My father didn’t understand my work. It made him uncomfortable. He felt I didn’t like men. He didn’t live long enough to see my books. [Hollander has written or collaborated on more than 20.] But what made me really sad was that he never lived to see me in a newspaper. He loved the newspaper. Every morning he had breakfast at the deli, a Danish, and read the Sun-Times. My mother did live to see what I was doing and get a lot of naches from it. Wherever she went, she said she was Sylvia’s mother.

I like when you get weird. You have two aliens in your strips.

Two recurring aliens. The Alien Lover is my idea of the perfect man. He cares about this human woman in a way I think most women want to be cared about. He’d bring the Artie Shaw Band back from the dead for her!

And then there’s Gernif, described in The Sylvia Chronicles as “an Alexis de Tocqueville, not from France but from Venus.”

I like science fiction! Gernif comments on the absurdities of human politics and life in our culture.

Speaking of absurdities, in the section on the earliest strips, you mention regretting depicting Reagan as a moron for so long, because it kept you from going deeper—for instance, questioning why the White House was so afraid of the Sandinistas taking control. Any other regrets?

In general I worry about missed opportunities. There’s so much information out there; I’m always worried about not catching something. Also, because of my deadline, I’m four weeks behind. So, I can only deal with politics if the issue will remain resonant a month later, when the strip runs.

Some of the strips—about corporate greed, environmental disasters, and health care reform—are as relevant now as ever. I like the one from 2003 set at the HMO Café, where a customer asks, “What’s the special?” and the waitress says, “A turkey club and a sigmoidoscopy … just kidding!” The customer gasps, “Oh, thank God!” And the waitress says, “We’re out of turkey.”

Thank you.

But as I read the book I was surprised at how I’d pretty much forgotten things that seemed so resonant not so long ago. The Promise Keepers, Alexander Haig, the Unabomber, Georgette Mosbacher—

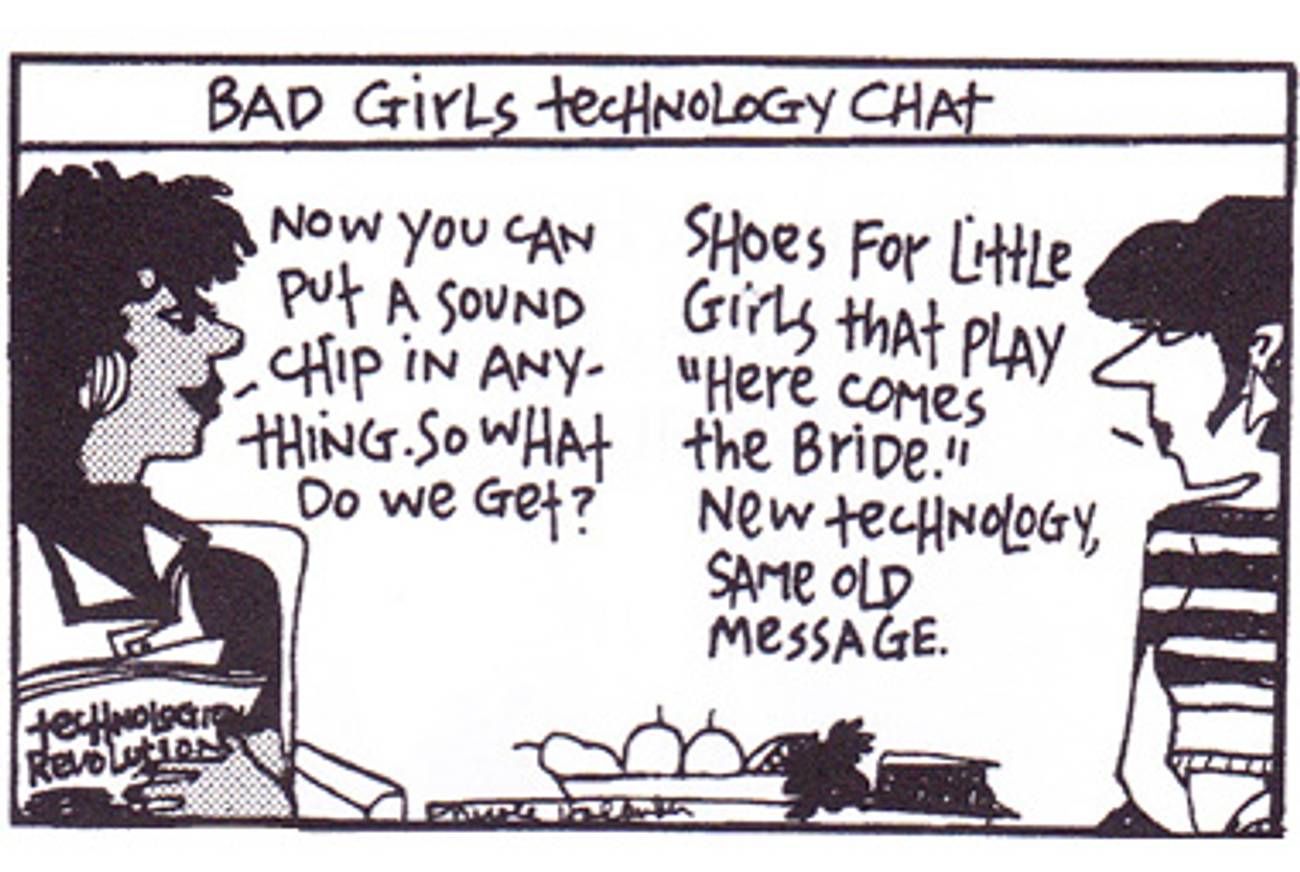

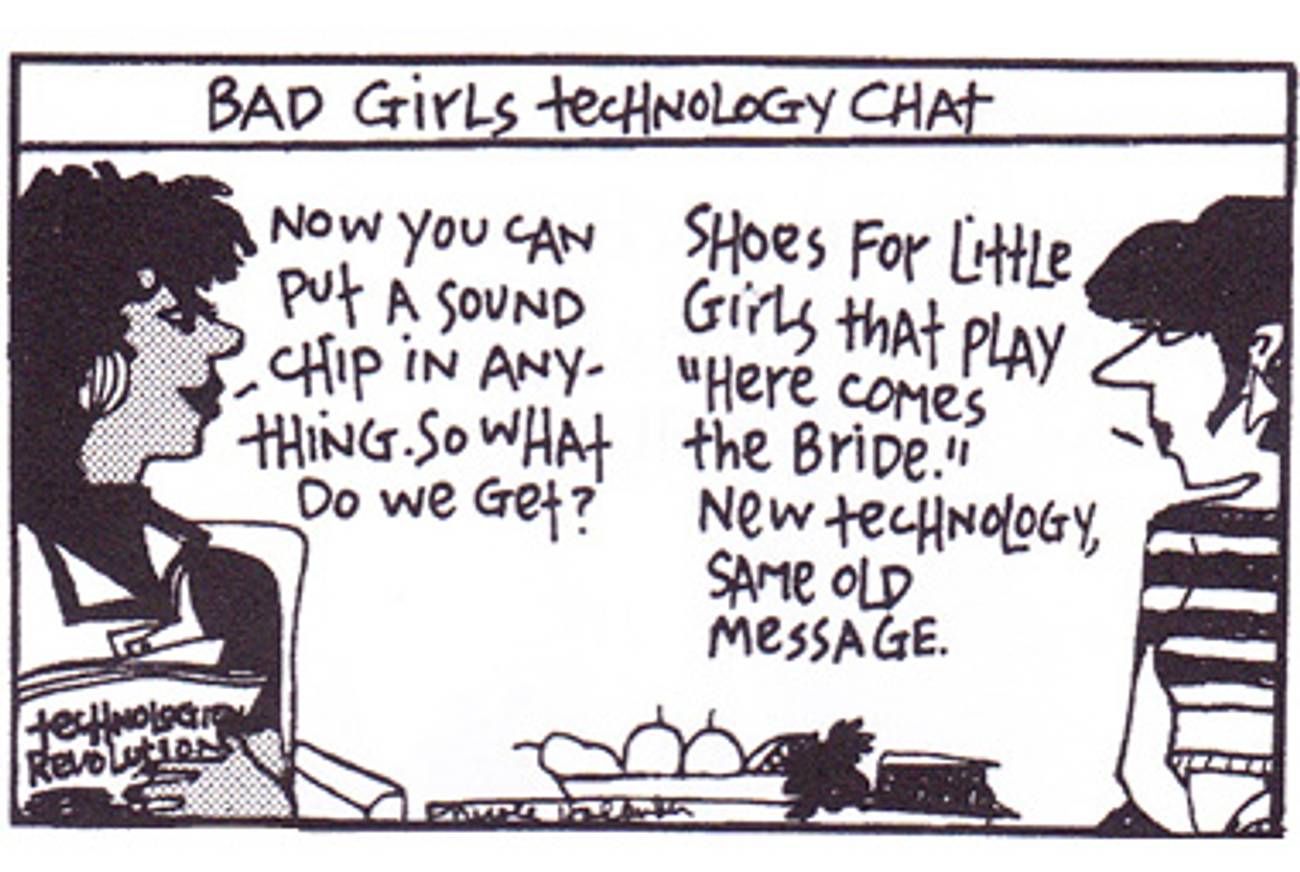

What surprised me was that our memories are so short. But what dismayed me was the number of different ways we could repeat the same mistakes as a nation. Things don’t change. The fight for women’s equality goes on. We say the world has changed because of technology, but advanced technology hasn’t advanced thinking. I don’t see that the relations between men and women have changed that much, other than stronger laws against chattel.

So, you don’t think we’re in a post-feminist era?

When did we get to the post-feminist era? Was I asleep, in a coma, or otherwise engaged?

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.