Real Estates

A haftorah of housing and holiness

If you’ve ever lived in New York, even for a spell, you’re likely familiar with the titillating genre commonly known as real estate porn.

It’s not that different from the fleshy kind: glossy magazines featuring intricately lit and carefully airbrushed spreads, measurements prominently displayed and met with oohs and ahs, fantasies of a more enticing life clouding the mind and quickening the pulse. Instead of naked men and women, however, real estate porn aficionados find delight in pictures of a classic six on the Upper East Side, say, or a pre-war co-op on Riverside Drive. In New York, dwellings often take on a spiritual significance, endowing the lives of their occupants with secret meanings and discrete charms.

The situation, you’ll be pleased to hear, was not much different in the Promised Land. In this week’s haftorah, we are treated to an intricately detailed description of Solomon’s Temple; those of us conditioned to consider an 800-square-foot apartment as spacious are likely to swoon.

“And the house which King Solomon built for the Lord,” we are told, “the length thereof was sixty cubits, and the breadth thereof twenty cubits, and the height thereof thirty cubits.” The haftorah goes on at length about, well, length and width, touting the Temple’s ample size as if it was not a description of God’s dwelling place but a listing for a Park Slope townhouse.

Why, we may be forgiven for asking, should we care? God, we’re told since we toddle, is everywhere, and omnipresent beings, presumably, should care little for cubits. But Jewish tradition is infinitely wiser and more intricate; even deities need domiciles, it tells us, because without bricks and mortar even the divine is at risk of being forgotten. The Temple, then, is not so much about an atavistic belief that God dwells in one specific edifice as it is about the symbolic acknowledgment that for our eyes to look heavenward, first they must see something beautiful and concrete. And because we’re forbidden graven images, a big building is a perfect solution. It serves both as the headquarters for the hierarchy of priests entrusted with our spiritual wellbeing and as an embodiment of our intricate relationship with the Almighty. Is it any wonder that so many of us have come to approach the real estate section of the local paper with reverence and awe?

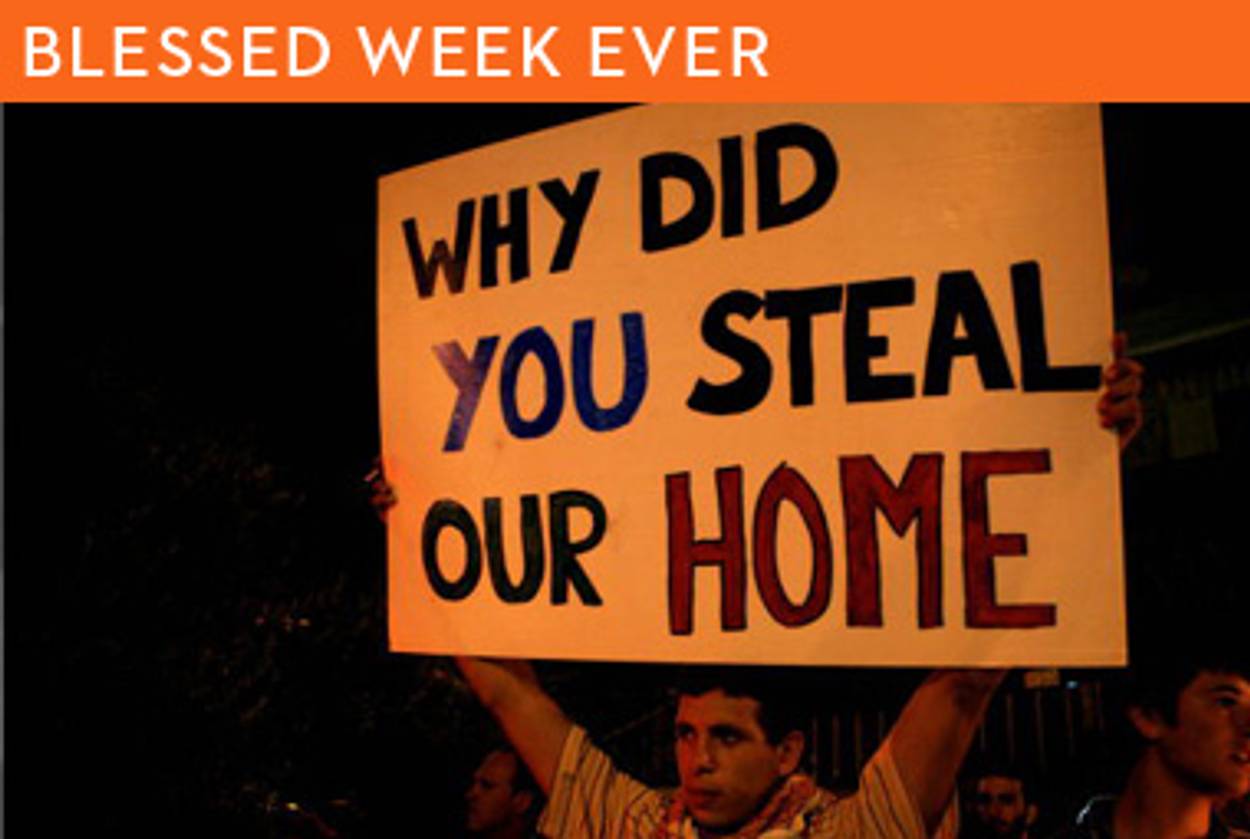

A similar appreciation for the inner spiritual lives of residential units was shown last summer in Israel. There, not too far from the site of Solomon’s doomed Temple, the Supreme Court ruled that several Palestinian families living in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of eastern Jerusalem could be evicted after a Jewish organization had successfully claimed that the houses in which they were residing were historically the property of Jewish families.

A bit of background is in order: in the late 19th century, a small Jewish community settled in the neighborhood, believing, as some Jews do, that the 4.5-acre compound they had purchased was the burial place of Shimon Hatsadik, a great high priest of the Second Temple. Arab violence in the 1920s and 1930s forced the Jews to disperse, and by 1948 none remained in the neighborhood. In 1956, the Jordanians, then East Jerusalem’s sovereigns, settled 28 Palestinian families in the compound. When Israel took over in 1967, these families were sued by the original Jewish owners; in 1982, the Israeli court ruled that the Palestinians were “protected tenants,” but that, as they didn’t own the property, they were required to pay rent to their Jewish landlords. The Palestinians, on their end, refused to accept this premise: if Israel started looking at who owned what piece of land prior to the state’s establishment in 1948, went the logic, it would have to concede much of its current territory to Arab refugees who fled the nascent Jewish state. Without incontestable proof of ownership, argued the compound’s Palestinian residents, no financial obligations are due.

Israelis saw things differently. A settler organization named Nahlat Shimon bought the land from its original Jewish owners and renewed the legal campaign to clear the compound of Palestinians. Incredibly, in the summer of 2009, the Supreme Court ruled in Nahlat Shimon’s favor, arguing that since the property was once owned by Jews, the original owners still held the rights to the homes they were forced to abandon decades ago.

With this, Israel erupted. Even moderates such as renowned novelist David Grossman took to the streets to demonstrate. Their argument was more historical than political; if the highest court in the land granted Jewish residents the rights to ancient homes, it could not feasibly deny the same rights to Palestinians seeking to take back their old dwellings in Jerusalem and Haifa and Tel Aviv.

Ir Amim, an Israeli non-profit dedicated to researching issues pertaining to Israelis and Palestinians in Jerusalem, was clear about the potentially disastrous repercussions of the court’s decision: “The legal recognition of the rights of Jews to sue for ownership over properties that were theirs before 1948,” the organization wrote in a report last month, “and in their name to evict Palestinian families living there for decades, constitutes a precedence that is liable to have serious political consequences. Indeed the Israeli law does not recognize the right of Palestinians to sue in a similar manner for the return of their properties within the Green Line from before 1948, but a collective lawsuit—if only symbolic—is liable to place the State of Israel in the most embarrassing situation in both the local and international arenas, in addition to transforming the discussion around solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from discourse around the 1967 borders to one around the 1948 borders. It is doubtful whether a process such as this will serve the interests of the Israeli governments.”

The authorities were unimpressed. Demonstrators in Shiekh Jarrah, Israelis and Palestinians alike, were arrested. They appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled the demonstrations legal. The Israeli police, as it often does, ignored the opinion of the court; peaceful protesters are arrested in Sheikh Jarrah still.

If any of them are unfortunate enough to spend this Shabbat behind bars, they may pass the time reading the haftorah. If they do, they’ll learn of the special spiritual connection between Jews and their buildings. Acknowledging this connection, Israel’s courts have opened the floodgates to an unimaginable deluge.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.