The Futurist

You might not have heard of Naftali Imber, but you’ve heard his most famous work

One of the convenient aspects of studying Jewish history is its 3,000-year-old paper trail—the texts and records of the rabbinical and intellectual elite allow us to examine contours of Jewish law and history. But in contrast, we tend to know less about the lives of average Jews, whose lives didn’t receive much attention in the writings of the intellectuals. That began to change in the late 19th century, when the Yiddish press hit the streets, for the first time recounting the lives of the unwashed masses of Jews in the public record. Tablet Magazine offers some of their stories, reconstructed from century-old newspaper accounts.

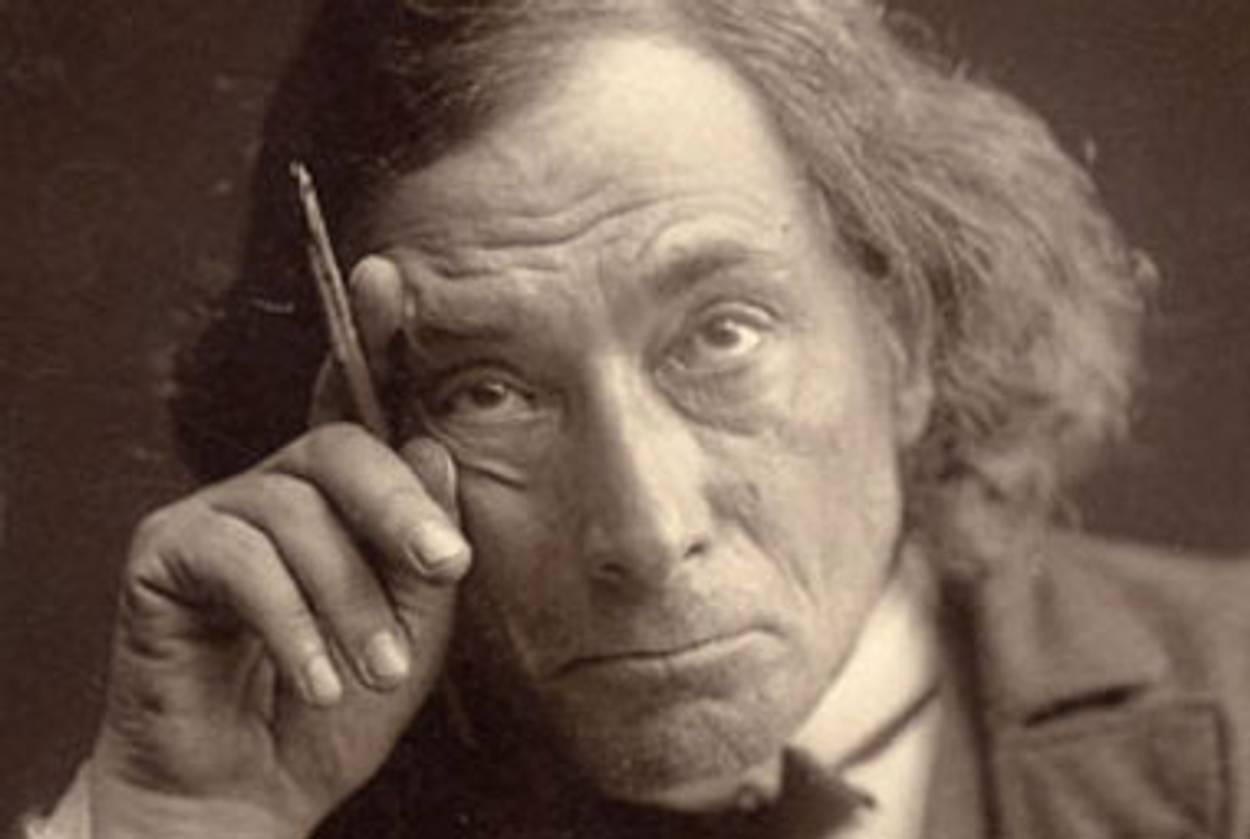

During the final decade of the 19th century, a man known variously as the Mahatma, and the “apostle of the Kabbalah and the Emissary of the 37 masters” traipsed around the Western United States prophesizing about catastrophes in Paris and future civil wars in the United States. With a leonine shock of gray-streaked black hair, he would stand before journalists and spectators and nonchalantly comment, “I’m going to shake the foundations of your world.” Whether or not his predictions shook those foundations is unclear, but he was popular enough to draw large audiences to his occult performances throughout the 1890s.

Before all that, he was a Hebrew poet and scholar known by the somewhat less exotic name of Naphtali Imber. Born into a Hasidic family in 1856 in Zlotshev, Poland, the same Galician shtetl that gave us the great Yiddish writer Moyshe Leyb Halperin, Imber was alleged to have been deaf, dumb, and paralyzed until the age of seven, when he underwent what could only be called a miraculous recovery and subsequently became known as a brilliant talmudic and kabbalistic prodigy. He also dabbled in poetry—a matter that might strike any Hasidic parent as boding poorly for his future as a scholar—and, in his teens, he wrote a poem on the occasion of Bukovina’s joining the Austrian empire that earned him an award from Emperor Franz Joseph.

A peripatetic young man, Imber broke out of Zlotshev while still in his teens and traveled throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire before leaving for Palestine in 1882, where he published Morning Star, his first book of poems. To earn his keep, he served as the secretary to the English adventurer Sir Laurence Oliphant, a Christian millennialist who, in an attempt to hasten the apocalypse, developed a plan in 1879 to lease the northern portion of Palestine for resettlement of the world’s Jews. Oliphant’s mystical beliefs influenced Imber, who left Palestine in 1887, returning briefly to Europe before leaving for India and, finally, the United States.

His American sojourn was marked by itinerancy and an increasing obsession with the occult. During a short stay in Boston in 1894, Imber married a local Brahmin named Kate Davidson, whom writer Israel Zangwill referred to as an “American Christian crank.” The couple went west, seeking audiences with other mystics, rivals whom Imber denounced as “bluffers.”

Dressing in a white gown, Imber offered remarkable predictions. In an 1896 report in the San Francisco Post, he warned Americans to stay away from Paris, where a disaster would soon occur. Within six months, an enormous fire broke in Paris’s Bazar de la Charité, the result of a film exhibition during which a projector set a pile of highly flammable film alight, killing hundreds and destroying many city blocks.

In 1897, at an event in Los Angeles, he predicted that in 50 years’ time, a Jewish state would violently come into existence in Palestine, and that, in the future, power from the sun’s rays would provide energy to heat homes and power transportation. A serious drinker, Imber also prophesized that California wines would one day rate among the best in the world.

Whether his prophecies always turned out remains to be seen. In October 1897, the Los Angeles Times reported on one of his visions: in 2010, he said, a new civil war would break out in the United States. Imber’s claim was that the ultra-liberal state of Kansas, whose female governor will have declared “the West for Westerners,” will secede from the Union. Kansas will be joined by Illinois and Missouri, prompting the Eastern states to launch a war against all of the Western states, which will have supported the secessionists. The West will rout the East, and the two sides will remain separate. The East, which will wage war with Canada and annex most of it, will be governed by what Imber called “the Manhattan Empire,” and the West, which will take on Mexico and annex most of it, will be governed by Chicago. Meantime, he said, California will split in two, with Los Angeles as the capital in the south and San Francisco as the capital in the north. Farfetched as Imber’s prophecy seems, its major question right now seems to be how quickly Kansas can become ultra-liberal.

Around the time Imber made his second civil war prophecy, he and his young wife attempted to settle in San Francisco, but, perhaps unable to compete with the memory of the city’s most famous Jew, Emperor Norton, and afflicted with the disease known as shpilkes, he left his wife, never to return. According to the Los Angeles Times, he resurfaced shortly thereafter in a Los Angeles police lineup after having been arrested for disorderly conduct in a flophouse where he was staying. Another resident had tried to hold him down and cut off his hair. Molested and mocked by onlookers, Imber went wild and, stalking the hallways of the place all night, screamed about cutting out his assailant’s heart. Imber stood with a black eye before the judge, the Times reported, and explained, “Conzidering ze zituation zat I was hit by a drunken man and called a little sheeney only to show ze anti-semitic feeling, is it any wonder zat I got angry, Your Honor?” He was found guilty and fined $20.

Imber then made his way to New York City, leaving his work as a seer behind and cementing his reputation as a poet, writer, and aspiring alcoholic. In their memoirs, Yiddish writers like Aaron Davidson commented on Imber’s infamous pub crawls. As an intellectual, he impressed philanthropist and judge Mayer Sulzberger, who became his benefactor and gave Imber a stipend of a dollar per week, doled out by the head of the New York Public Libraries Jewish Division, Abraham Freidus, a bug-eyed fat man, known to patrons as “the hippopotamus.” Freidus, a brilliant bibliographer who suffered from a glandular disorder, would stick Imber’s dollar in a book and have it delivered to Imber at his table at the library. Imber apparently spent more time at the library than at home: on his 1905 passport application, he gave his address as “New York Public Library.”

But hard drinking and hard schnorring had taken their toll. After Imber’s death in 1909 at the age of 54, one of the eulogies in the Yiddish newspaper commented that he was the only true Jewish bohemian. A few days later, a letter appeared noting this fact was wrong, that Imber was not a Bohemian at all and, in fact, from Galicia.

Although his history as a clairvoyant and knife-wielding drunk is not particularly well known, Naphtali Herz Imber was never an unknown quantity. He became famous, after all, as the eminent author of “Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem, a ditty he first wrote while on the road in Romania in 1877. He tweaked it when he got to Palestine, publishing it as the poem “Tikvateinu” (“Our Hope”).

Eddy Portnoy, a contributing editor for Tablet Magazine, is the Academic Advisor and Exhibitions Curator at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is also the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press.

Eddy Portnoy is academic adviser and director of exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, as well as the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford University Press 2017).