A Trip to Ukraine Reveals My Family’s Connection to a Literary Legend

Visiting Odessa, the city where I grew up, I learned how Isaac Babel turned my great-great-grandmother into an iconic character

These days, Odessa is all over the news. But it is a specific Odessa—one of chaos and street clashes; one where children may be evacuated for protection; one with low wages, zero-based production demand, and rising unemployment; one with over a million citizens, some of whose embattled photos dominate the front-page news during Ukraine’s intense struggle for self-definition.

Last summer I took my older daughter, Anna, to see a different Odessa—the one where her father grew up. It was the Odessa that was supposed to be a “porto franco”—a free city that would attract talent and wealth to benefit this “New Russia” that enabled German Jews like my grandfather’s ancestors to bring with them European culture and Reform Judaism and start a new life there. That is how Odessa became a cradle of modern Russian culture, in large measure because of the Jews.

The current Russian-Ukrainian conflict is not about Jews, though it may put an end to that piece of Jewish history—which will be a loss for everyone. But before Jewish Odessa disintegrates, it had one more unexpected gift for me: a literary pedigree.

***

The basis for our trip was a visit undertaken by a delegation of the World Zionist Organization. I took the visitors on a tour of the Jewish Odessa of my family, who were contemporaries and comrades of Pinsker and Jabotinsky.

Later that week, Anna and I were taken around by my daughter’s namesake, Anna Aleksandrovna, who is the deputy director of Odessa Museum of Literature (is there another one of those anywhere?). This Anna had endless stories to tell, seemingly about every building and chestnut tree. Here lived Russia’s greatest poet Alexander Pushkin, here the incomparable David Oistrach studied the violin, there Duke De Richelieu built his first palace …

As we were walking, I pointed out my grandparents’ home, the apartment where I grew up. “Look up,” I told her. I pointed out #2 on Catherine the Great Street, named after the tsarina—who was not actually Russian, but still reigned from 1762 until her death in 1796. In fact, Odessa—the only large city in Europe built around a theater, not a fort or a church—was founded at her behest. Her favorite, Prince Potemkin, became associated with the city because his name was on the rebellious battleship that shelled Odessa in 1905. Her statue as well as her name on the square our balcony looked over and the street our building was on were replaced during the Soviet era first by those of Karl Marx and—when the statue of Marx kept mysteriously tipping over—by a heavy granite monument to the rebellious sailors of Battleship Potemkin. Yes, the Battleship Potemkin of the Eisenstein silent movie classic with a child’s carriage riding down the grand staircase to the port I knew as Potemkin steps.

My grandparents, parents, and I shared one room in this communal apartment with shared public spaces—a kitchen and one bathroom—to accommodate us and five other families. The one bathroom had six light bulbs, each with its own switch, and six separate toilet seats, one for each family. The apartment once belonged to my great-grandfather, and one of its rooms was kept in the family right up to our departure for the United States in 1975. And that was only because my great-grandfather was a physician with a specialty in treating venereal diseases and was thus much in demand by the “reds” and the “whites” and the “greens,” as the various armies were known during the civil war after the Bolshevik revolution.

We were considered lucky. We had a balcony and our own telephone.

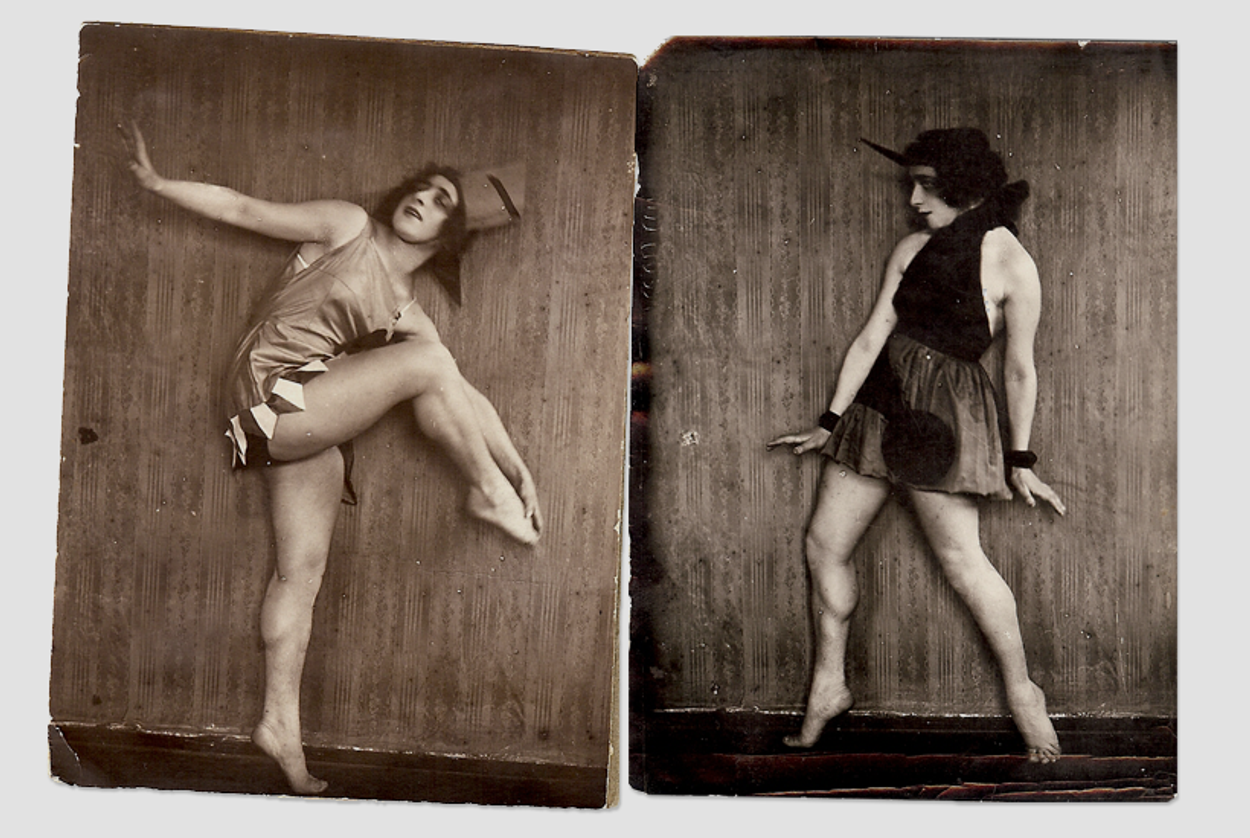

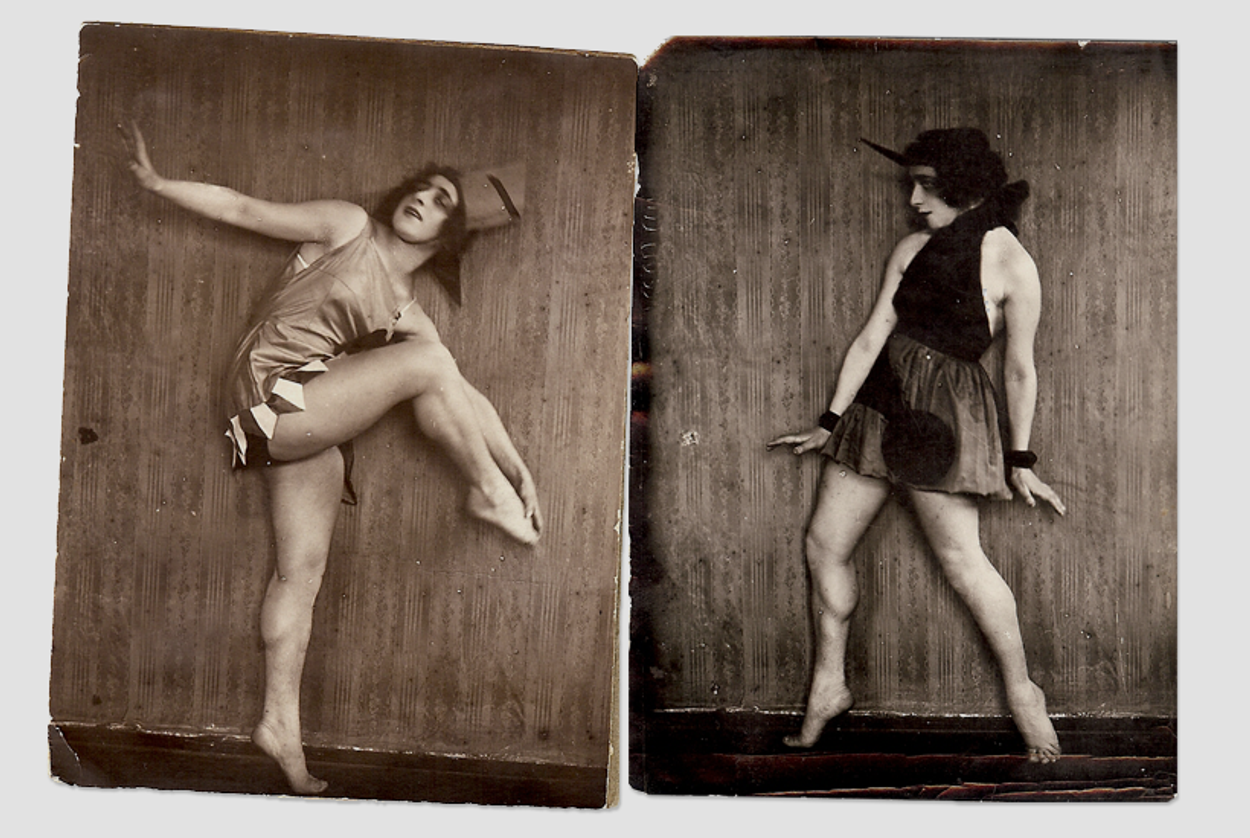

I shared my nostalgic enthusiasm with our tour guide and she asked about the family. I told her about my grandmother—Sofia Reingbald, a chamber dancer, “the Isadora Duncan of Russia” and teacher of movement and dance for 50 years at Odessa’s famous Stolyarsky School of Music just down the street from our apartment building. I have a poster hanging in my house announcing her solo concert, and my younger daughter is named after her.

The guide was so excited by this news that the next day she made a point of finding Anna and me, at which point she handed us a copy of a book called Madam Lyubka, by Rostislav Aleksandrov. It was about Isaac Babel—the iconic Russian Jewish writer, the quintessential Odessan—and how he came to write his Odessa Stories.

Babel was born at the end of the 19th century; his family lived in the more fashionable part of Odessa. But because of the Jewish quota at the time, Babel could not get a place at Odessa University (a fate I, too, would suffer in the 1970s). He became a successful writer nevertheless, working in journalism and then later as a playwright and short-story writer. He wrote Odessa Stories, using my neighborhood and others as the backdrop for many of his tales of daily life and drama. (Stalin, ever fearful of intellectuals—had him shot in 1940, putting an end to Babel’s great literary imagination.)

Perhaps the most important story of Babel’s collection, reprinted in the Aleksandrov book the guide gave me, is about Lyubka the Cossack, a proprietor of the inn in Odessa’s Jewish working-class district and sort of a godmother of Jewish teamsters, thieves, and rabble. I had, of course, read the story. But I hadn’t ever heard its backstory.

Madam Lyubka is the seminal character in Babel’s tales—and the personage around whom Aleksandrov’s narrative about Babel’s writing is built—but she is hardly sympathetic. Babel’s Lyubka the Cossack and Other Stories is set in Moldavanka, which has been called the thieves’ district of Odessa. The central character, Tsudechkis, makes a financial deal with a landowner and brings his new partner to Lyubka the Cossack’s inn for a drink to settle the deal. She is not a Cossack; it is an “affectionate” nickname. The landowner has a piece of gefilte fish and then a tryst with a prostitute and then leaves at dawn without paying. The watchman is furious and locks Tsudechkis in Lyubka’s room until he pays the bill. The watchman claims that the innkeeper will thrash him upon her return. Tsudechkis is indignant, comparing Lyubka to Pharaoh and believing that just as God saved the Jews from the Egyptians, he would save poor Tsudechkis from the clutches of Lyubka. In Lyubka’s room, he sees a crying baby, the innkeeper’s son, and another woman who is busy reading the Tales of Ba’al Shem Tov and ignoring the child. She claims that Lyubka is out buying contraband and cavorting with Russians in bad business. Tsudechkis takes the baby in his arms until Lyubka comes back with her tart mouth and acerbic wit, unable to nurse her son. Tsudechkis weans the child and is finally let go in exchange for a pound of American tobacco.

On page 120 of his book, Aleksandrov notes that in 1974, the real-life Lyubka’s last surviving granddaughter—Sofia Reingbald—still lived at #2 Catherine the Great Street.

This was too much. My walk down memory lane soon felt like a surprise airlift to literary notoriety—albeit one removed from me multiple times over, like hidden knowledge of a distant cousin once removed that is suddenly revealed. My family was not shy about sharing history. Why had no one ever told me this?

Perhaps they were ashamed. There she was, our matriarch—my great-great-grandmother—the godmother of Odessa’s Jewish teamsters and thieves. I also understood why my grandmother, one of the most refined and vain women I ever knew, never told me about her. Lyubka married off her daughters and her granddaughters to the upper class of the Jewish community, the German Jewish intelligentsia. I heard plenty about them—physicians and engineers and early Zionists. But not about Lyubka.

But I am not ashamed. I loved Babel’s Lyubka and how colorful she was. She reminds me of a freer time on those once magical streets, where conmen ate gefilte fish and the procuress of an inn read the tales of a tzaddik. Stalin had Babel murdered, but his stories lived on. In Odessa today, the scoundrels are back, but they are not Babel’s fictional scoundrels. They may yet destroy this place.

Today only about 30,000 Jews are remain in Odessa. In my time—40 years ago—there were perhaps 300,000. The last pogroms took place here in 1905, and the Nazis murdered thousands in 1941. But all those Jews who were Odessans when I was growing up have mostly left for Israel and other points west.

In the end, our tour was not a walk down memory lane but down history’s lane. Our family story is different today. We have our own toilet, even more than one, and they have their own seats, and we live spaciously and free, without the demon of violence over us. But there is a shadow over our brothers and sisters in Odessa right now. Nostalgia has turned into anxiety. I suppose it’s time to make life better somewhere else; time to close the doors on #2 Catherine the Great Street and celebrate from a distance what life there once was, back when my great-great-grandmother Lyubka used to dream of a different future for her brood.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Dr. Misha Galperin, a clinical psychologist and CEO of Jewish Agency International Development, is the author of The Case for Jewish Peoplehood and Reimagining Leadership in Jewish Organizations, published by Jewish Lights.

Dr. Misha Galperin, a clinical psychologist and CEO of Jewish Agency International Development, is the author of The Case for Jewish Peoplehood and Reimagining Leadership in Jewish Organizations, published by Jewish Lights.