Taking the Plunge

I visited the mikveh and became a Jew. But I still haven’t told my dad I converted.

Last week, I visited the mikveh and completed the formal process of conversion to Judaism that I began almost two years ago. I’ve told most of the people who are close to me about this change, but not all of them. I’ve told close friends, relatives, and colleagues. I’ve told my children. But I have not told my father. Not yet.

As for many proselytes, the catalyst for my conversion is a serious romantic relationship. But unlike, I think, some of my fellow converts, I have yearned to be Jewish since I was in my early teens, and I’ve spent decades suppressing that desire even as it continued to inspire my way of experiencing spiritual and religious truth. Judaism, I recall thinking at a very young age, offered a purer essence of God, uncomplicated by the idea of the trinity. And it was not only a faith but also a nation, a community of people united by shared beliefs and a shared destiny.

When I was 12, for example, I asked one of my friends if I could go with her to Hebrew school, and, if I did well enough, if I could have a bat mitzvah. She looked astonished, almost shocked, at the idea, and then laughed at me. Then she grew very serious. She said no, I could not become Jewish. She said a person had to be born Jewish to be Jewish. She waved her hand at my blond hair and blue eyes, visible evidence of my Scandinavian genetic inheritance. Ever so gently, she confirmed her verdict against my becoming Jewish, but this time she did it by casually including a word I had never heard before: shiksa.

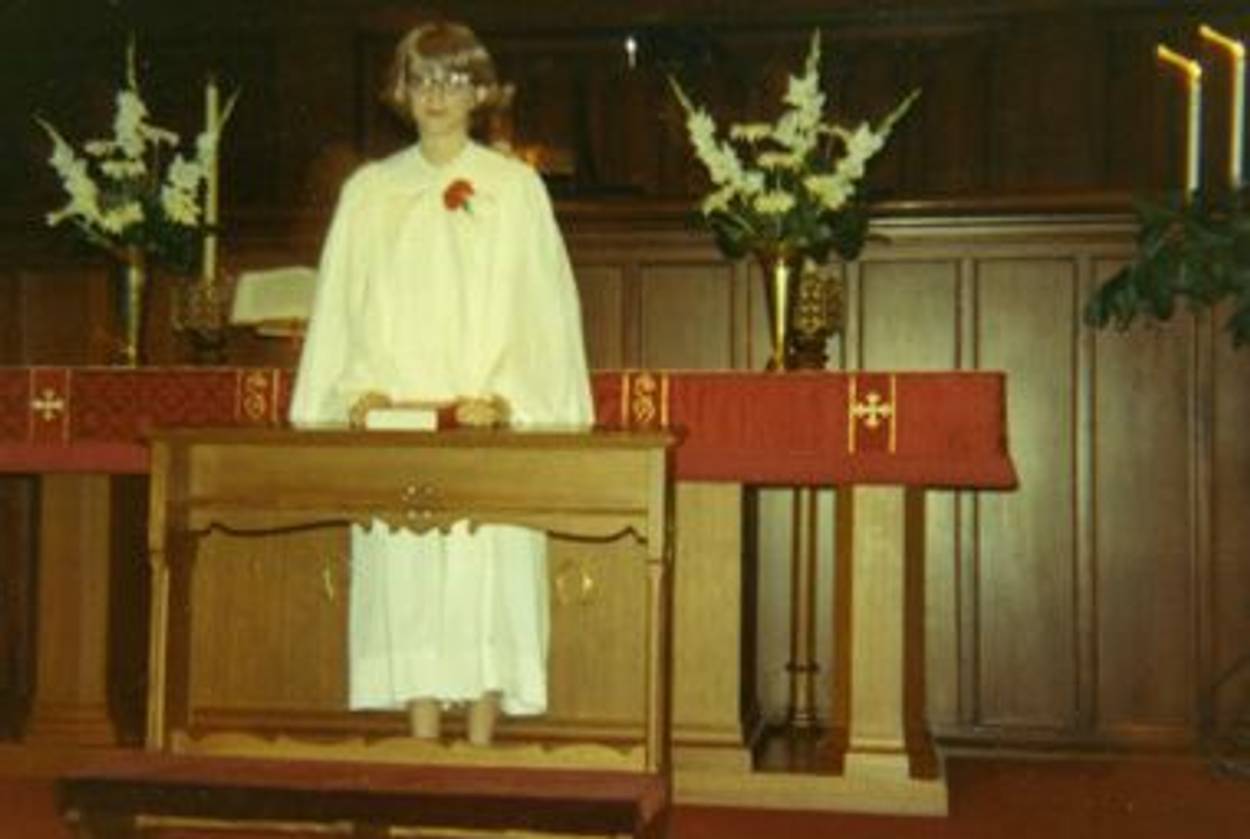

So I remained in the church my father had introduced me to, attended Sunday school, services, and Vacation Bible School, memorized Bible passages, sung hymns, played Mary in the Christmas pageant. But the gap between what I did to meet the expectations of the adults around me and what I believed in the privacy of my own head and heart, had become wide and deep. And I couldn’t become Jewish, I thought as a teenager, I could at least seek out Jewish people as my friends.

This caused my parents concern. “They’ll never accept you,” my mother said, as I prepared myself for that rare, but oh-so-desired occurrence—a date, with a guy who happened to be Jewish. “You can go out with one of them, but don’t ever think about marrying one. They never let their children marry outside their religion.”

I ended that conversation with my mother as quickly as I could, but her verdict was confirmed by conversations with my closest Jewish girlfriends. They agreed with my mom—no mother of any Jewish guy I dated would be happy that he was dating me. Those parents would be on guard, watching for any sign of the relationship becoming serious and would make sure it went no further. This was Dayton, Ohio, in 1972. And although there had been, to my knowledge, no openly expressed resistance to the religious diversity of my public high school, by dating the boys I wanted to date—Jewish boys—I was forced to recognize that invisible barriers still existed, separating Jews from non-Jews.

So I remained in my community, got married, had two children and raised them both in the Christian faith. I wanted a place and a life that connected me to God, and I wanted a community where my family could live out that connection. I knew my personal beliefs did not align with the religion I “belonged” to, but I tried to make the best of what I felt was available and acceptable.

Once they were in their early teens, I mentioned to my children that I had always had a desire to be Jewish. I made reference to some amount of tension between my beliefs and the religion we practiced. But I’m sure I talked about it the way an old person talks about how he or she once wanted to be a poet but ended up selling insurance.

A few years later my husband and I divorced. My children were almost grown by then, the older one in college, the younger one on his way. I was over 50 years old, at a true pivot point in my life. Then, unexpectedly, I reconnected with a friend from my college days, who was also divorcing. He was Jewish, but he had not been observant at all in college. Now he was. In one unforgettable conversation two years ago, I asked him a million questions. I expressed my envy of his religious practice, the life he now had. He looked at me pointedly and asked if I would ever consider converting. I shrugged and nodded, suddenly blinking tears. Then I sat back, realizing I could actually do it. Freed from past constraints, societal and personal, I could accept his invitation.

At the age of 52, I finally began my studies to become a Jew. It didn’t take long for me to become overwhelmed. I was flummoxed by Hebrew and sometimes humiliated by my confusion during services. But everything I learn about Jewish practice and theology and ethics and history delighted me and fit into my heart like it had always been there. Last year I made my first trip to Israel. I went to the Western Wall—a long-held dream. I wept and prayed and laughed and felt like I had come home.

I told my children about my intention to convert as soon as I began studying with a rabbi. They were not surprised at all. They were, and are, happy for me—essentially they see it as my own personal decision. They have expressed some amount of curiosity about what I’m learning and doing. We have celebrated Hanukkah together and lit Shabbat candles a couple of times, but they are distracted by their own lives and their efforts to make the transition to adulthood. They are both going through an agnostic stage and have no interest in attending any kind of religious services. And they are of that generation that looks at differences that my cohort used to see as immutable—differences like religious beliefs—and sees them as flexible pieces of identity to be emphasized or de-emphasized, accepted or changed, at will.

And yet, I cannot bring myself to share my happy news with my father. I think he probably knows that conversion is a possibility, that I might become Jewish because I am in a relationship with an observant Jew. In phone conversations, I have mentioned—casually but frequently—attending synagogue, giving and going to Shabbat dinners, a conversation with a rabbi. But he has asked no questions.

I certainly don’t expect anger or rejection from him. I’m sure that he will feel disappointment as well as concern for my “salvation”—which is still very hard to for me to take. My father is in his early 80s and has been a church-going Christian his entire life. I’m not happy about the prospect of causing him distress at this point. He helped raise me in his faith, passed on his values, and I like to think I have always been a comfort to him.

So I have postponed and procrastinated. I would wait, I told myself, until after the fact, until I dipped in the mikveh, until I was officially Jewish. Not that it matters all that much; whenever I do decide to tell him the news, I know that he will suffer in silence those worries he might have about my soul and its destination. And, being a parent myself, I know I can’t relieve him of those worries.

I have been so full of emotion during this countdown to the mikveh. I have waited so long for this moment, which makes it hard to be distracted by anything else. This is my choice, the fulfillment of decades of yearning for something behind a closed door. The door opened, and I have walked through and immersed myself in a life I have always wanted.

I want to believe that all those who love me will celebrate that choice. Maybe someday they all will.

C.A. Blomquist is a writer, editor, and artist who lives in Manhattan.