A Dip in the Mikveh, Nearly Derailed by Fake Eyelashes, Was Vital to My Conversion

The whole idea of a ritual bath seemed foreign and too religious. But now it’s a warm reminder of the moment I became a Jew.

After I decided to convert to Judaism, people started asking: “Are you going in the mikveh?” They spoke with raised eyebrows, their voices dropping into a whisper at the word, mikveh, as if it was an opium den.

I learned on the Internet that the mikveh is a ritual bath that some observant Jewish women visit every month after menstruation and that the mikveh is also used by men and women alike before major life events, such as marriage or childbirth. I asked the rabbi who’d been teaching me whether I’d be going to the mikveh as well. “Oh yes,” she said, noting that it’s often the final step of a Jewish conversion. “You’ll definitely be going in.”

Except I wasn’t sure I was a ritual bath kind of girl. The whole idea seemed antiquated and out of sync with my modern life. But a quick dip in the mikveh ended up being one of the most meaningful moments of my conversion.

Like many potential converts, I was seeking to become a Jew for love. My fiancé and his Reform Jewish family were not strictly observant, but Judaism was important to them and I wanted to share a religion with my future husband; besides, I didn’t have much of a religious identity of my own to leave behind. Before deciding to convert, I identified myself as agnostic; my parents and I had given up practicing Protestantism over 20 years before.

So, after we got engaged last December, my fiancé and I started attending Exploring Judaism, our Midtown Manhattan synagogue’s prerequisite course for prospective converts. Every Wednesday night, we gathered with two dozen other students in a Hebrew-school classroom to learn the ABCs of the Jewish faith. Most of us were within five years of 30, couples with one Jew and one potential Jew. The name cards spread out along the U-shaped table tended to alternate Old Testament names, New Testament names: Jacob and Mary; Leah and John.

A rabbi who wore crisp sheath dresses and had smooth blonde hair—and wasn’t much older than the students—taught the class. Despite her perfectly put-together exterior, she had a disarming warmth and sincerity and gave off a comforting sense that when she wasn’t on-duty, she might get into sweat pants and pour herself a glass of wine. One night, after a few rounds at post-class drinks, we all confessed that we had become smitten with her. “I know Judaism doesn’t do saints,” said one soon-to-be-ex-Catholic, “But if it did, she’d be one.”

I felt completely comfortable connecting with Judaism on an intellectual level in class. I liked reading about the religion’s historical foundations, and the lively discussions during Exploring Judaism felt almost like graduate school. The mikveh, though, was uncharted waters. None of my born-Jewish friends had ever actually been in one; even my fiancé wasn’t exactly sure what it was. And the idea of a ritual purification seemed very, well, religious. For someone for whom chanting Namaste at the end of yoga class was for many years the closest thing to a spiritual practice, the mikveh was a big escalation.

Perhaps naively, when deciding to convert I had focused on the cultural aspects of Judaism—the warmth I’d always felt in Jewish families, the food, the sense of humor. In those ways, I already felt Jewish. My fiancé and I knew we wanted to celebrate major Jewish holidays, and through our Exploring Judaism class, we learned that we enjoyed carving out a night of “Shabbat” each week to just be with one another. But how and if we planned to observe in other ways was still a discussion in progress.

And though my parents were completely supportive of my conversion, by choosing to become Jewish, I was also choosing to become different from them and to do things that were foreign to them. Aware of this, I was always looking to reassure them that my conversion was not going to change things, that I would still be their daughter, only Jewish. But what would my nonreligious parents think of me going in the mikveh?

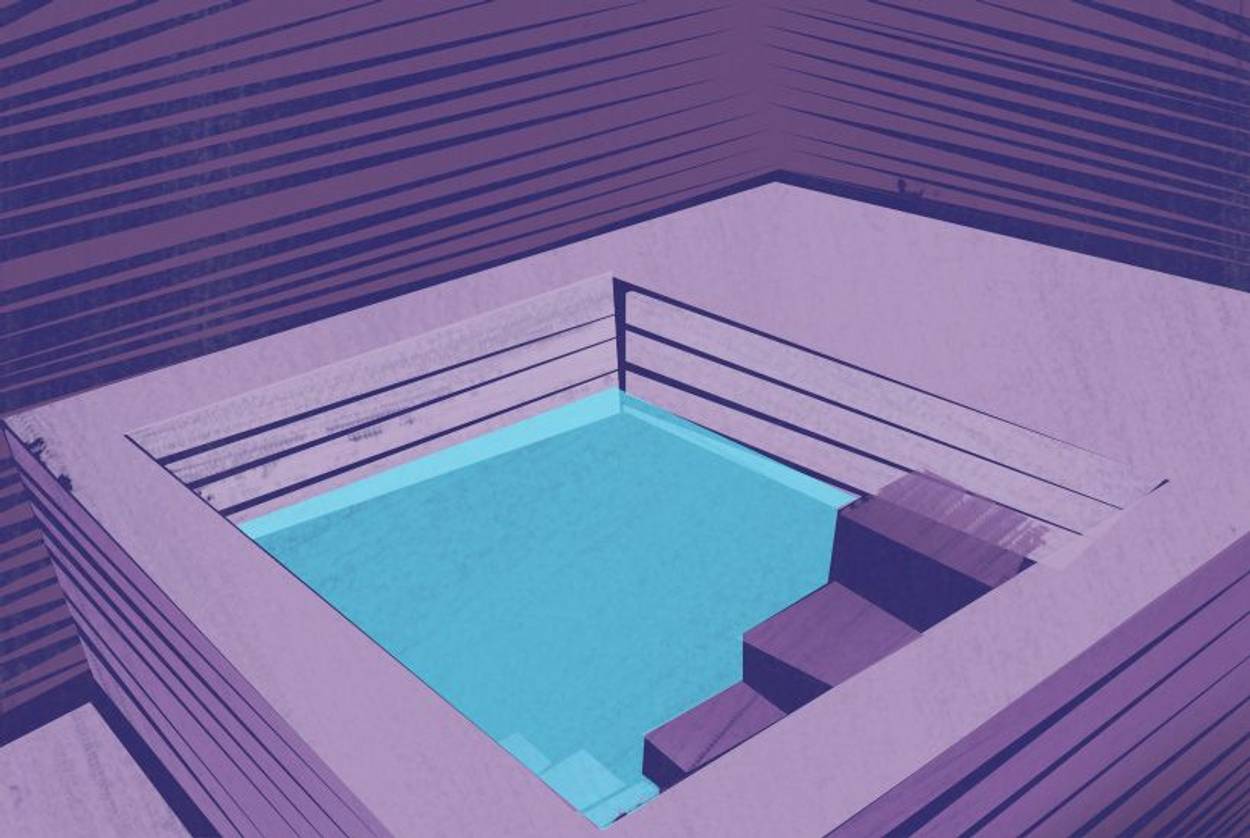

When I called up my mother to tell her about the aquatic portion of my conversion, I quickly directed her to the mikveh’s website, which had photos of the changing areas and the mikveh itself. “Oh,” she said, sounding relieved, “It looks just like a spa.”

But there was one other problem. While I was preparing for conversion, I was also deep in the throes of last-minute wedding planning. In a fit of bridal vanity, I had gotten semi-permanent eyelash extensions. A few days later, I realized my potential folly when I read over the mikveh instructions my rabbi had sent me: I needed submerge in the water completely naked—without jewelry, make up, nail polish, or even contact lenses. There wasn’t anything specifically in the instructions about fake eyelashes, but I had to think they might be a no-no.

I called the mikveh that I planned to visit and asked for Gita, the attendant who handled conversions. “I’m so sorry to bother you, but I’m coming into your mikveh for my conversion next week,” I said. “I’m getting married, and I got these eyelash extensions that don’t come off for a month. Is it OK to wear them?”

“Eyelash extensions? No problem, honey,” Gita said, as if she’d been asked the same question 10 times that day.

For some reason, Gita’s nonchalance affected my anxiety, which began to fade. Though I found out later that her answer was based on a principled distinction between foreign substances that can easily be removed from the body and those that can’t, what I felt at the time was that there was a sense of accommodation of the reality of people’s lives—even a bride thinking she needed silk fibers glued to the ends of her eyelashes—that calmed me. The mikveh would accept me, eyelashes and all. And I realized that the mikveh didn’t have to be this intimidating, foreign thing; going in the mikveh was for me and would be what I made of it.

On the morning of my conversion last July, I had that particular nervousness of being close to a categorical change. Everything I did was full of significance. Next time I eat cereal, I’ll be Jewish, I thought to myself. This is my last time loading the dishwasher as a Protestant.

After lunch, my fiancé and I walked to the mikveh, which was located in a nondescript brownstone on Manhattan’s West Side. My beit din, or “rabbinical court,” where I was questioned by my Exploring Judaism rabbi and two of her colleagues about my decision to convert and my studies, was held in the waiting room. Then Gita appeared and led me to an immaculate, white, private dressing room.

Once I’d showered and dressed in the provided white, waffle-cotton robe, Gita led me into a room with a small pool, maybe eight feet square, tiled in dark gray. At least, I think that’s what it looked like—without my contact lenses, I could only really make out a watery blur. As I blindly padded over to the water, I remembered what my rabbi told me: “Once you’re in the mikveh, you’re coming out Jewish.

The water felt body temperature, almost silky, and wading in, I was immediately reminded of the unique wonderfulness of skinny-dipping.

“OK, honey,” Gita said once I was all the way in, and pointed down with her finger. I inhaled, held my breath and went under, lifting my feet off the floor into a sort of fetal position as I’d been instructed, so that the water reached every part of my body. When I couldn’t hold my breath any longer, I popped my head above the water as Gita yelled, “Kosher!”—signifying that my dunk was good to the rabbis who were listening at the door.

As soon as I had wiped my eyes and gained some semblance of composure, Gita cued me to start the first prayer. Then it was time for another dunk. When I emerged from the water the second time, I was legitimately out of breath. As I came up for air the third and final time, I heard, at first muffled and echo-y, and then clearly, Gita and the rabbis belting out, “Siman tov and mazel tov, mazel tov and siman tov!”

When I had changed back into my street clothes, my fiancé, the rabbis, and I gathered back in the waiting room and one of the rabbis sang the final blessing. As she sang, I began to cry, my tears pooling on the floor with the drips from my still sopping wet hair and my extended eyelashes clumping together. I was Jewish. How I lived out that change and what it meant for me day-to-day was something I still had to discover. But I would never forget the moments when the change happened. If my conversion had simply been marked with the recitation of a Hebrew prayer or a celebratory dinner, the memory would have inevitably become fuzzy. But the mikveh made the day I converted unlike any other day. And whether I ever went back, I was grateful to the mikveh for taking me out of my life and starkly demarcating the time I became Jewish.

When the ceremony was over, my fiancé and I walked out onto the street. I held his arm with one hand and clutched the envelope with my official certificate of Jewishness in the other.

“Mazel tov!” someone on the sidewalk said when we’d gone a few steps.

We both looked up, startled, to see a man in his thirties grinning at us. How did he know? Was it that obvious? Was I just radiating an unmistakable, new Jew glow?

“I’m next,” he said, and walked past us into the brownstone.

Leigh McMullan Abramson is a freelance writer living in New York City.