Finding My Grandfather, and Myself, on the Battlefields of the Spanish Civil War

He joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in 1936, as a Jewish teenager from Brooklyn. This year, I retraced his steps.

This summer I stood with some 80 people on a hilltop outside Madrid, our guide narrating the 1937 battle between the fascists and Republicans for the olive groves and crumpled tan valleys below. My group—some waving banners for anarchy and labor—included a high-school teacher, a documentary crew, a few Irish and English, and one octogenarian who had fought there, in the Spanish Civil War’s battle of Brunete. Between us we represented most of the Republican alliance that tried (and failed) to stop Franco in Spain: the descendants of Spanish Republicans, European Internationals, modern-day leftists, anarchists, and me, the apolitical grandson of David Dombroff, a radical American socialist.

I had come to Spain and to this memorial march for an answer: Why had my grandfather, then a skinny Jewish teenager, traveled from Brooklyn to fight in this dusty countryside 76 years ago?

While we walked, I told the others what little I knew of my grandfather’s involvement. David Dombroff shipped out for Europe in the belly of a commercial liner on the day after Christmas 1936. At age 17, by family accounts, he was one of the first 96 members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade—Lincolns, as they called themselves—and he was fairly typical of the 3,000 or so who would follow. Many were leftists, a third were Jewish, and hundreds were recruited in New York by the Communist International. Close to a thousand died in Spain, but my grandfather survived.

The story of the Lincolns seems little known in America, buried in part by the subsequent backlash against communism. In the Spanish hills, though, a reverent audience surprised me. To these people my grandfather was part of a vanguard, a volunteer who fought in Europe long before his country joined WWII. Almudena, a woman in her early forties who’d coordinated part of my trip, said she cried when she met her first Lincoln. One man told me, in accented English: “Do not forget your grandfather.”

To me, forgetting wasn’t the problem. I was trying to remember a story I’d never really known.

The idea of a trip to Spain took root just after last New Year’s, though I didn’t know it yet. I’d booked a flight from North Carolina to see my paternal grandmother in Texas, worried by her sparse phone calls. Her condition worsened before the trip, and by January the doctors were talking about hospice and end-of-life treatment. Somehow, though, she was awake and waiting when I arrived at her hospital room with my cousins.

We asked about the past, because we didn’t know what else to discuss. She could still name all the girls in her collectivist dance group from the 1930s, and she told us again about her friend who was a famous photographer from the Photo League cooperative. She talked about the cultural foment of New York City during the Depression, when the Communist International recruited freely in New York for a pan-racial labor alliance.

She told me too about David Dombroff, the boy she met at a proletarian summer colony in upstate New York—the one who’d fight in Spain and marry her a decade later, after the wars were over. I’d heard the outline of these stories for years, but to see her so close to death reminded me how little I knew.

A few months later, by coincidence, my parents began planning a family vacation to Barcelona. It was my mother who put the idea in my head that maybe I could see our past. I started, of course, with Google. First I searched for “David Dombrov,” as I thought his name was spelled, and found a Wikipedia page with an ancient photo of a rabbi who looked kind of like me. A couple variations of the spelling—Dumbrov, Dombrof, Dombroff—brought me to a list of Jews who served in the Spanish Civil War’s International Brigades. And there was David Dombroff, 68 Bay 32nd St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

He was one of about 1,200 Jewish people on the list. The author, an archivist for the Jewish Military Museum, argued on the web page that it was Jewish ideals about equality and duty that drove a lot of these guys to Spain. This was an appealing thought. My mother’s not Jewish, and I wasn’t raised with any religion, but I’ve always imagined, or maybe yearned, for some connection to Jewish culture.

Eventually, I reached the email list of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. I sent David’s passport number and his name and begged for help. A few days later, a man with the email moniker “captainlaser” wrote me back: He had found David Dombroff on the passenger manifest for the Lincolns’ first boat to Spain.

With a few more emails, I had contacts in Spain—and I decided that after our family vacation, I would take the bullet train from Barcelona to Madrid to see these people and places. I felt like I was undeleting family memories.

The finale of my summer expedition came two days after the group tour at Brunete. That morning I headed to Madrid’s central train station to meet Severiano, a historian, a teacher and a leader of the Asociacion de Amigos de las Brigadas Internacionales. I’d arranged a small second outing to Jarama, where I believed my grandfather had fought.

We rode out of the city in Seve’s white subcompact around 10 a.m. In the backseat were Eddie, a sun-chapped Irishman, and Peter, an English newspaperman living abroad, both of whom I’d met at the memorial march two days earlier. We passed once more into the tanned hills outside the capital. In one village, my companions pointed to the flag of Franco’s Nationalist regime on a second-story wall. It was a banner for the other side of the ghost battles some still fight in Spain.

We stopped at a crossroads marked by white signs: Chinchón, Morata de Tajuña, San Martín de la Vega—all names I recognized from The Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a thick, yellowing history book I’d found. Severiano led us up a steep embankment above the broad-cut valleys.

“This is where your father was,” he said. My grandfather, I reminded him.

My books said this hill was the site of the Lincolns’ terrifying first contact with the Nationalists and their allies. Sweeps of machine-gun fire had pinned the largely untrained men as they tried to dig the crude trench where I stood. I spun with my camera, trying in my brief opportunity to process anything at all.

Then we piled again into the subcompact and swung down to the edge of an orderly olive grove. Here would have been the Lincolns’ suicide run, where the North Americans were ordered to charge lines of machine guns in their first major action. None of the historical accounts conclusively place David Dombroff in that action—I can only assume he was there based on the dates of his entry to and exit from Spain. Maybe, I thought, he rushed the defenses or carried casualties back, or ran to hide with the shell-shocked deserters.

Eddie knew the land, so he said he’d walk me through the battlefield’s olive grove. We marched from the car onto a farmer’s dusty plot, Eddie and Peter walking ahead of me while Seve drove around. I knew even then how absurd the whole thing was. Not having many family histories or traditions, I was trying to write one. And the journey to find one’s secret past, I knew, was a clichéd set-up.

But it did kind of work. I paused for a minute in the middle of the grove. I felt briefly like I could remember the shouts and the gunfire and the buzzing of insects, and I knew the short olive trees were old enough to have stood through the massacre too. Standing, sweating, I conjured this sensation that I was finally sharing something with a man I never knew, from a time I couldn’t understand.

What I saw when I opened my eyes was a field where ideology and the pull of war brought young men over trench walls. Scores of Lincolns died there, and thousands more soldiers in the surrounding terrain, but they changed little in the outcome of the war, and little stands to mark their ends. Near the groves, at least, there was only an impoverished memorial of fragments and barbed wire

No place is holy by itself, I realized. Battlefields like Gettysburg only feel like hallowed ground because we’ve given them markers and names. Near the river Jarama, there was nothing but what I’d brought and learned.

Before I left I took leaves from the olive trees, for a keepsake. During our drive back we stopped at a huge metal sculpture of clasped hands, strapped with wilted flowers and circled beneath by wartime tunnels. A monument to the international brigades, it reminded me of the goodbye Dolores Ibarruri, the Republican Pasionaria, gave to the foreigners as the republic crumbled in 1938: “You can go proudly. You are history. You are legend.” (Others didn’t remember the Internationals so kindly, and some websites to this day claim that the Internationals were murderous revolutionaries.)

Our tour ended in a museum back in the tiny town. The proprietor welcomed us in the front hall, next to a huge sculpture of a man smelted from battlefield scrap. Photos lined the walls, bullets in dusty glass cases, guns and bayonets, all collected by this old man, grinning and posing for a photo with his metal soldier. Like the others I met, he was a keeper of memories.

I ended my time in Madrid with Almudena and her boyfriend. We toured the University district, where spiders live in scores of machine-gun bullet holes. We saw spray-painted hammer-and-sickles, and they showed me the secret markings of the fascists, the engraved honorifics for Franco, and a monument to the International Brigades that may be torn down. We parted ways near the edge of the city center, at a small plaza overlooking Franco’s faux-Roman victory arch. Everything was gray, the sky especially.

Almudena told me there were old fascist bunkers in the park just beyond the arch. One more stop for a tourist, I thought. The two of them made closed-fist salutes as they walked away. “Don’t forget your grandfather,” Almudena told me.

Alone again, I felt like I’d just washed ashore. I scribbled as fast as I could in my journal. I wondered what my grandfather would have thought of all this, the political currents that picked him up still circulating around. He was only in Spain for six months, while, I’m told, most of the Lincolns stayed through the conflict or died in Spain. Our family story says that David’s mother somehow convinced the communists to bring him home once the first fighting was done. Still, even after my grandfather’s death, his friend for years would bring my father—David’s son—to the Lincoln veterans’ meetings. The Lincolns themselves would remain a politically active organization for decades, at times blacklisted and at times honored.

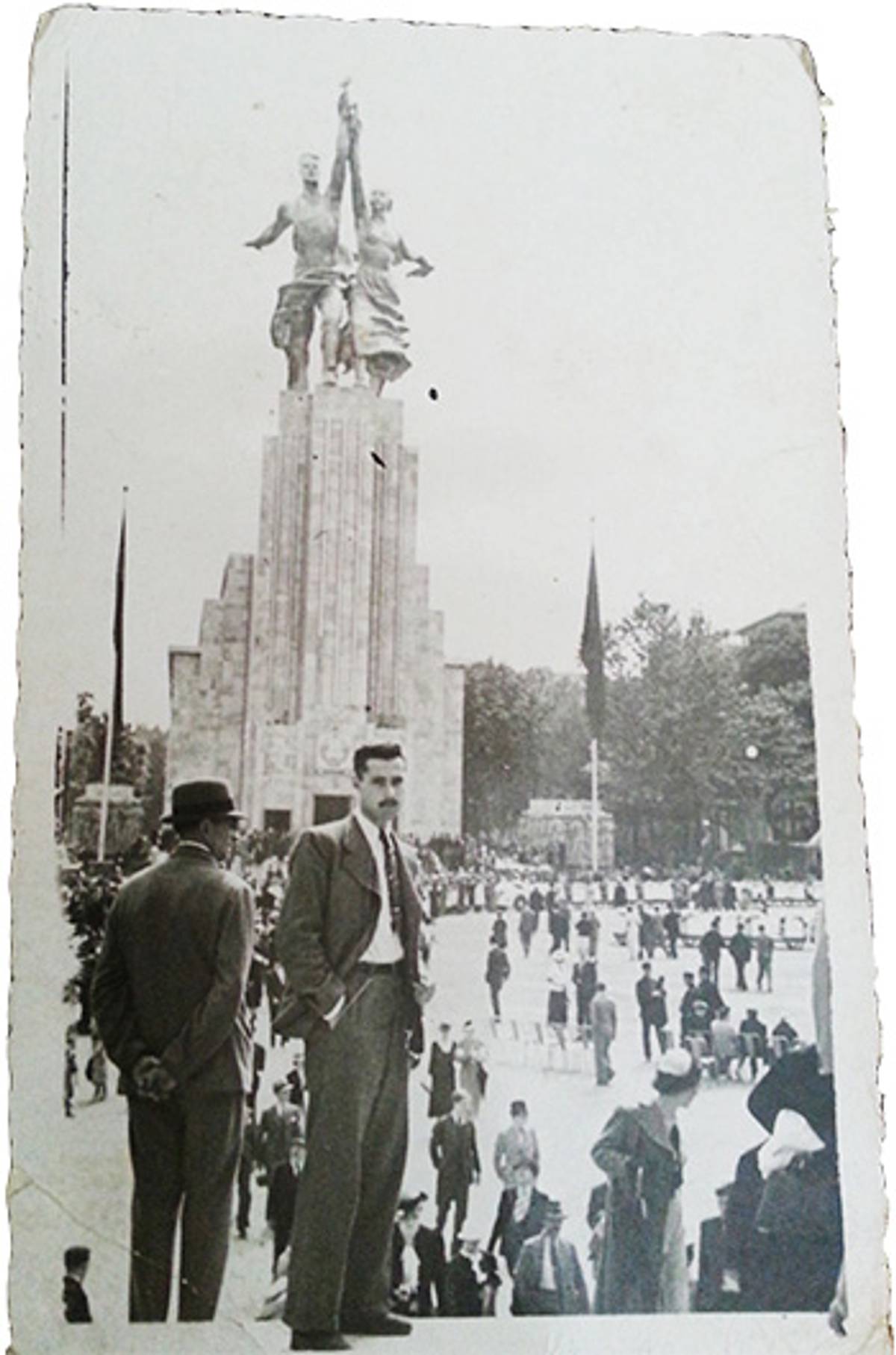

My mother found a picture of my grandfather just before I went to Spain. He poses in perfect focus, tall in a baggy suit, tie clipped and tucked into his shirt. There are hundreds of people milling around in the plaza that drops out behind him, and a man in profile just to his right. He’s the only person whose face isn’t blurred or obscured. His hair’s combed straight up, and he has his children’s eyes. Far behind him, there’s a dominating statue of a man and woman lifting their hands together.

It was the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, I later learned. He was standing before the Soviet pavilion, just across an avenue from the Nazis’ huge, symbolic gate. He would have stopped there on his way home from Spain that June, before he took the steamer from Le Havre back to New York. His face in the image doesn’t say much to me—he’s proud, maybe hardened, maybe cynical, standing in the city the Nazis would take three years later, at the seam where the world was coming apart. It may have been the first clear image I ever saw of him.

A few years later David Dombroff would change his name to Richard Kenney. We don’t know why. Doesn’t that speak to the confusion in our line? Our identity itself shifted, perhaps to escape the communist witch hunt that began even before WWII. Although they celebrated Jewish holidays, he and my grandmother didn’t take my father to regular services, nor did they make him a bar mitzvah—though anti-Semitism in a rough neighborhood may have discouraged them.

From what I know, my grandfather was an impassioned young man, or zealous. He came from a different time, when the stakes were higher and perhaps the dividing lines were bolder. He’d go on to serve on a WWII bomber in the Pacific, the sole survivor of a terrible crash. As he recovered, he complained in a letter about others’ passive stance toward the war, and he boasted of the Japanese Zeros his plane shot down. Grandma, though, says he cooled after the wars. He collected coins and fathered three boys in his last decade, before he died late in the 1950s.

Unless we uncover some trove of letters, I’ll never understand exactly why David Dombroff volunteered for another people’s war. I won’t know what role his religion played, and I won’t draw any conclusions about what parts of his spirit may have passed down the line. But I at least felt more rooted as I wandered the Spanish coast at the end of my trip, hoping that for a day I had seen what he saw.