Since a panel of religious scholars warned last summer that the script of The Passion of the Christ would yield an anti-Semitic film, Mel Gibson’s self-financed Aramaic-language feature has been a subject of escalating controversy—and media hype. But many of the issues raised by the film, which opens February 25, belong to longstanding discussions about the representation of Jews in the Gospels, the history of Passion narratives, and relations between Jews and Christians.

James Carroll is the author of Constantine’s Sword: The Church and the Jews, as well as ten novels, most recently Secret Father, and a memoir, An American Requiem, which won the National Book Award. Alan F. Segal is a professor at Barnard College and Columbia University and the author of Rebecca’s Children: Judaism and Christianity in the Roman World, Paul the Convert, and Life After Death: The History of the Afterlife in the Religions of the West. James Shapiro is a professor at Columbia University and the author of Shakespeare and the Jews and Oberammergau: The Troubling Story of the World’s Most Famous Passion Play.

Early coverage of Gibson’s Passion has focused on arguments about whether particular lines should be cut from the script. But is there any way to tell the story of Jesus’ death that will satisfy everyone?

JAMES SHAPIRO: When you fiddle with a script, there’s a fantasy that you can produce a Passion play that is not offensive yet is moving emotionally for audiences. What takes place on screen or on stage transcends the script. I’ll give a specific example: Matthew 27:25 [“Then the people as a whole answered, ‘His blood be on us and our children,’”]; this will only be in Aramaic, and not in subtitles. Jewish groups were able to get Oberammergau to eliminate this line from their script after decades of negotiation. But when I saw the Oberammergau Passion play in 2000 and sat behind Rabbi Leon Klenicki of the Anti-Defamation League, I watched him cringe during the scene in which the Jewish crowds collectively called for the death of Jesus without saying that line.

JAMES CARROLL: The sacred texts of every religious tradition are words written to be spoken and heard—even more than to be read, I would argue—and the oral experience leaves the power of the imaginative interpretation to the hearer. That’s not true in cinema. I’m reminded of the ancient human intuition to be somewhat skeptical of images. People of various cultures—Hebrew culture for a time, certainly Mediterranean cultures more broadly—were so powerfully devoted to the skepticism of images that we had idol smashing. Iconoclasm, literally. Whether you’re talking about a Passion play or a rendition of the Passion story on film, it doesn’t matter whether the script can pass some kind of litmus test because the script is thinly related to the experience that viewers are going to have.

ALAN SEGAL: In working on The Gospel of John, the advisory committee worked mostly with a script and a screenplay. When you actually work on a film, you have to make allowances for the fact that several people on the film have their own artistic independence, especially the director, but also some of the producers and the costume people.

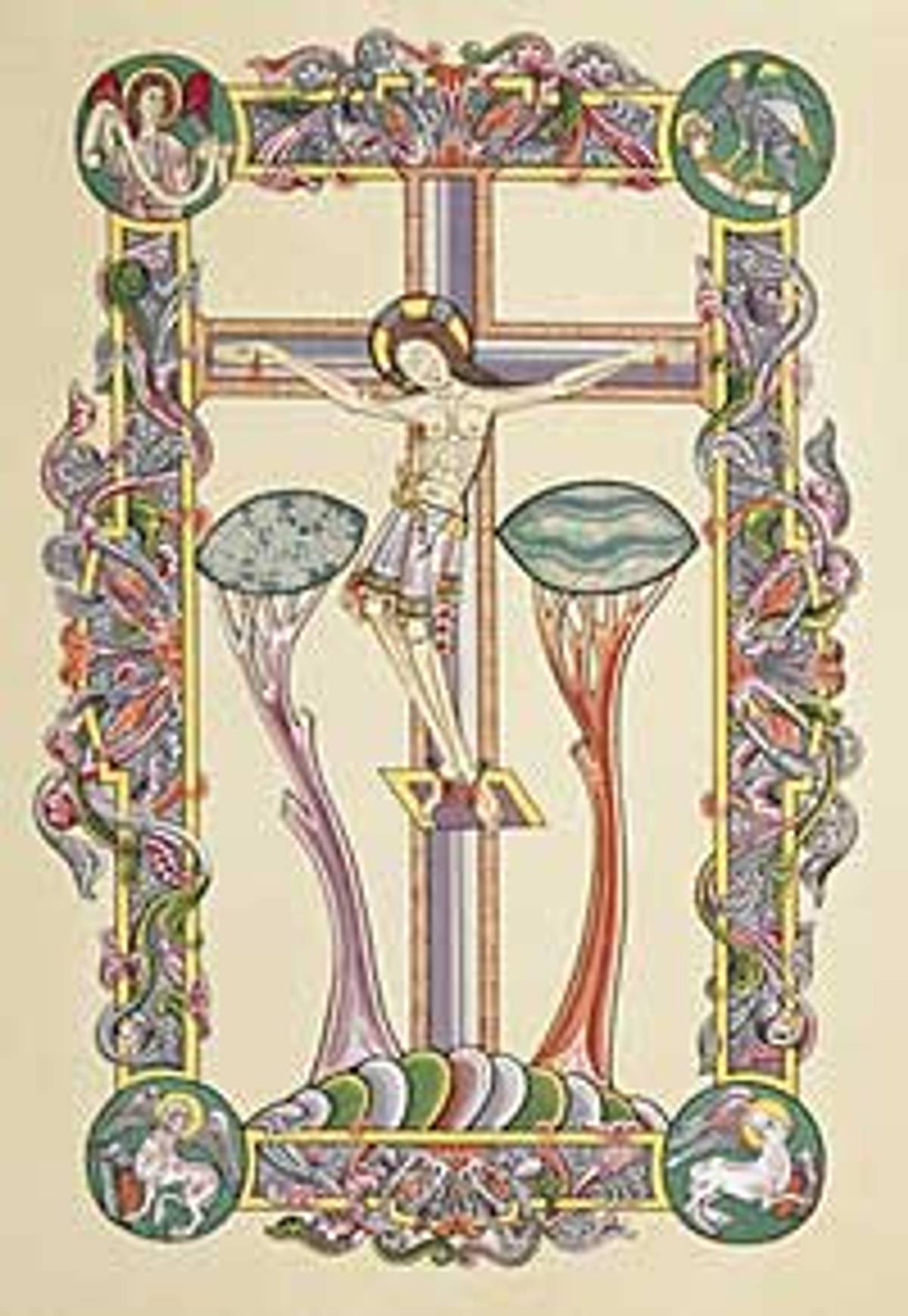

SHAPIRO: The Gospels say in a single word Jesus was crucified. That word does not provide the complex imagery that people who read the Gospels need. I think there’s too little attention right now paid to the extent to which Mel Gibson is indebted to a series of stock images that he can’t break from, that seem timeless, that seem 2,000 years old. They’re probably half as old as that, and are themselves shaped by anti-Jewish polemic in the Middle Ages. It was only in the 11th and 12th centuries that narratives began to explore what the Passion looked like: How many wounds did Jesus receive? Was the crucified Jesus in an S or a Z shape? Was his body twisted? Where did the nails go? All those issues were worked out over a couple of centuries that had tremendous implications for Christian art, sculpture, Passion plays, music, poetry.

CARROLL: The crucifixion comes vividly into the Christian imagination tied to the great theological statement that God sent Jesus into the world precisely to die. His death is the entire purpose of his coming, St. Anselm tells us, because only his death could atone for the sin of human beings. And it’s not at all an accident that this theological affirmation comes in 1098, just as the saving act of Crusader violence has been launched by the Church. The Crusaders, on their way to attack the enemy abroad, first attacked the enemy at home, which was, of course, the Jews.

SHAPIRO: Those Passion narratives were produced at a time when Jews were accused of host-desecration or poisoning wells or other kinds of crimes, but the tradition also speaks to the rift between Christians and Jews because these Passion narratives drew on scripture typologically to fill in the details. You could read the Psalms and find evidence for Jewish bestial behavior. It’s a very complicated story of how we now visualize the timeless Passion scene. But it has a history. And that history deserves closer attention right now.

SEGAL: On the other hand, one can still ask hard questions about the screenplay. When Jews watch a Passion play—or even read the Gospels, which are a much broader experience in which Jews can actually participate, because they see their own history being reenacted, albeit in a kind of unusual way—the first question they ask is, “Why is there so much negativity in this story about Jews?” In the classic texts of rabbinic Judaism, which Jews may or may not be familiar with, you don’t find very much discussion of other religions. You might find a couple of potshots taken, but you never find the arguments characteristic of a great deal of Christian scripture. And so Jews, the first time they read or watch the foundation stories of the Christian community, they’re really taken aback.

CARROLL: The Gospel writers drew up a story in which the conflict was essentially between Jesus and his own people, partly because of historical reasons: a Christian community within a broader Jewish community that was rejecting their claims. But also, I think, simply because of the power of that narrative choice. In Christian memory, it’s very easy to read this as a story of this one man against his whole people. And once the Christian movement forgets that this man was himself Jewish, it becomes very easily read as the Gentile Jesus against the Jewish community that rejects him. It isn’t just a problem of the Passion narratives. It’s really the way in which the Gospels themselves are read and remembered.

SEGAL: Why do the Jews become more and more the fall guy? I think the answer has to do with the empty tomb tradition. The resurrection is not described in the New Testament. Nobody witnessed it. And, as you look through the Gospels, you discover that the Jews are the ones used to underline that an empty tomb is not the same as a resurrection. When the Jews are blamed for starting the story that the body has been stolen, the evangelist is objectifying early Christian doubts as demons to be exorcised. The Jews were the only people who expected a messiah, and when Jews doubt that Jesus was that messiah, it is a big theological problem for early Christianity.

CARROLL: When a Hindu denies Christian claims, it is not a threat because Christian claims are based on the Jewish precedent. We believe that Christian faith is a fulfillment of Jewish hope and expectation. When Jews broadly repudiate it, it’s mortally threatening, which is why, I believe, down through the centuries, Jewish rejection has been so devastatingly threatening to Christians, that it has generated such inhuman—and at times murderous—responses. There’s no obvious equivalent on the other side; Christian rejection of Jewish claims have no particular impact on Judaism, precisely because Judaism doesn’t have any dependence on Christian faith.

SHAPIRO: There are bit characters that have appeared over time in the history of Passion playing, characters like the Wandering Jew, who reputedly struck Jesus on his way to his crucifixion and was told he would walk forever. And he walks for thousands of years, penitentially. He begins to appear in the Passion play as an eyewitness, as a Jew who resolves doubt for Christian audiences.

In Constantine’s Sword, James Carroll, you mentioned an 1119 Papal bull in defense of the Jews that was reissued by more than 20 popes. Why is this still a problem for the Catholic Church?

CARROLL: Well, don’t forget that the reason it was reissued by more than 20 popes is that it continued to be a problem. The popes wouldn’t be issuing bulls forbidding the physical attack of Jews if Jews weren’t being physically attacked. It’s a noble tradition for the Catholic hierarchy, down through the centuries, to defend Jews and forbid things like forced conversions, even when they were quite a powerful impulse among Christians. But the bishops and the popes never found it possible to get at the theological, ideological sources of such behavior.

Why was it that on Good Friday, year in and year out, Christian congregations poured out of cathedrals looking for Jews to attack? Because the bishops, while forbidding such attacks, never dismantled the supercessionist theology that defined the moment of Jesus’ death as the moment of Christian triumph over Jewish denigration. That’s the moment, in the anti-Jewish structure of the Christian imagination, between the old covenant and the new covenant. And it’s a short jump to go from a covenant that has no reason to exist to a people that has no reason to exist. The theology that ties all notions of Christian salvation to the death of Jesus is still more or less intact, certainly among the people who are appealed to by this film.

SHAPIRO: Will there be a point at which the Pope and Vatican officials decide that there’s a danger of losing Catholics to Evangelical groups through films like this? Or is there a sense of comfort with the kind of theology that’s behind this film? What’s not being asked is to what extent Mel Gibson is asking the Church to roll back the clock. The Church has been silent, and that silence is read, at least by people like me, as agreement.

CARROLL: What’s at stake in this film, and how it’s received, is the tremendous progress that’s been made in Jewish-Christian relations over the last 50 years. Any disproportionate emphasis on the death of Jesus removed from the context of his life is somehow going to be at the expense of Jews. Mel Gibson is not being careless. The reforms of Vatican II are incompatible with the kind of theology of the death of Jesus that he has put on screen. I’m desperately longing for powerful Christian responses to this film to help people think critically about it and to make very clear that the strong anti-Jewish overtones of the film are fully repudiated, even though they’re rooted in the Gospel texts.

Is the real problem, then, not that Mel Gibson isn’t faithful to the Gospels, but that the Gospels aren’t faithful to history?

CARROLL: Gibson asserts, in defense of the film and the choices he’s made, that he’s just showing it, as he puts it, “the way it was.” And there was the quote attributed to the Pope, that the Vatican later denied, that “It is as it was.” The point is that even a minimally historically aware person understands that it isn’t as it was. The Gospels are not the work of eyewitnesses.

SEGAL: There’s a lack of sensitivity of film critics to whether this is an accurate representation of the Gospels, and whether the Gospels are an accurate representation of what happened. They also assume that one can be accurate to the Gospels in a single film. They don’t realize how different and contradictory the portraits of Jesus are in the Gospels.

SHAPIRO: With a film of a Jane Austen novel, they’ll say, “This wasn’t in the novel.” But I think that we probably make a mistake in assuming that there is an educated group of people in America who know the Scriptures and can speak in an informed way about what’s being done. There are very few people who can do that, and even fewer of them are speaking out.

CARROLL: The most important thing any viewer could have in mind is that it’s a story being told by the grandchildren of the people who experienced it. The Gospels were written down 40 to 60 years after the death of Jesus; John, with the most savage depiction of Jews, was written down 70 years after. And all any of us have to do is think of the stories we tell in our families about our grandparents’ generation. Those stories are composed out of family love, out of family pain, out of love for the old country that was left behind. The Mel Gibson rendition absolutely obliterates those distinctions in time.

Scholarly interest in the historical Jesus, as opposed to the Jesus of the Gospel narratives, has blossomed in the past 30 years. How does what we know about the historical Jesus shape the way we think about his death?

SEGAL: We don’t know with any kind of surety all the things we want to know about Jesus. What we do know, strangely enough, begins with the inscription on the cross. Almost everybody believes that “King of the Jews” is an accurate inscription, because the Church has no interest in telling you that Jesus is king of the Jews. That’s something that makes sense only to a Roman, certainly not to Jews. So this is the kind of thing that passes all our tests and that speaks directly to who bears responsibility for the death of Jesus. That there were Jews who pressured the Romans into doing it—all of this is surmised and doesn’t pass any historical tests.

CARROLL: The critical fact of the historical Jesus is his Jewishness, which is a shockingly obvious thing to say. But it’s largely forgotten in the Christian memory that Jesus lived and died as a faithful—what we would call Orthodox—Jew. And every hope he had was hope within the context of Israel. And the God he honored and worshiped was the God of Israel, nothing but. My own strong conviction is if Christians had remembered that in a vivid way, the history of Jewish-Christian relations would be very different. Christianity would not have found it possible, even in the first century, to demonize a group called the Jews if we had maintained a lively hold on the fact that Jesus’ loyalty to this group was absolute.

SEGAL: Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet, somebody who was trying to wake Jews up to a new way of being Jewish underneath Roman domination, a person who spoke out strongly for purifying the Jewish religion. The Jewish people were in very dire straits because Roman domination was even more cruel and difficult than it had been in the past. So it’s no accident that we begin to get messianic hopes at this period. Jesus wasn’t the only messianic candidate of the time, and was but one of thousands of Jews crucified by the Romans.

SHAPIRO: The terrific scholarship that was nurtured in the aftermath of Vatican II is not, from my perspective, getting the same support from the Church right now or from the academy, which tends still to be highly secular. My colleagues in the Columbia English department are not Bible readers, are not people who take religion as seriously as the American public might. I think Mel Gibson’s film may be a dagger in the heart of the historical Jesus, as odd as that sounds.

CARROLL: The largest failure of the Catholic Church has been its failure to bridge the gulf between what scholarship takes for granted and what people in the pew know and understand. The chasm between Christian scholarship on one side and Christian piety on the other, between Christian intellect on one side and Christian faith on the other, is quite destructive. The Second Vatican Council began to address it. While John Paul II has resolutely affirmed the possibility of reconciliation between Jews and Christians, other broader theological positions he’s taken—his broad abandonment of the reform movement of the Second Vatican Council—have, in the long run, undermined the capacity of the Church to leave behind its tradition of contempt for Jews.

SHAPIRO: The strongest argument I know against a historical Jesus and the academic study of the historical Jesus is that it ends with the crucifixion. Because you can’t talk about a resurrection historically. And yet that’s such a central part of what Jesus is and means. Mel Gibson’s not interested in challenging the historical Jesus by making a movie that represents a resurrected Jesus for more than a moment or two.

SEGAL: He’s depicting the Passion, but he leaves out Jesus’ entire mission as described in the Gospels. What you have left is a deeply emotional experience, with people divided against each other. But if you look at Jesus’ mission and his preaching, even as represented in the Gospels, you see that he is part of the Jewish community, speaking lines that have a position within the Jewish community, even if it’s mediated through the perspective of a writer.

SHAPIRO: Then why is there no one in a position of religious authority saying, “Where are the teachings of Jesus in this film?”

SEGAL: Why don’t movie critics say that? They seem to say, time after time, this is the Gospel according to Mel Gibson. But it’s not a Gospel at all, as you’ve been pointing out. It’s a Passion narrative, a Passion play. When you tell the Passion story, rather than a Gospel, you are cutting out a whole bunch of the context in which Jesus lived and taught as a Jew. The overall effect is to make it more dualistic, with Jews serving as the bad guys.

CARROLL: And it posits the absolute significance of suffering. And that’s actually what one would have to call in the Christian tradition a kind of heresy. It is making the death of Jesus the entire purpose of his life, instead of the moment that ended his life—really a perversion of everything we know in the Gospels about Jesus. Down through the centuries, again and again, the Christian message has been reduced to the absurd notion that suffering is the purpose of God’s plan for human beings.

SEGAL: And here, I think, all three Western traditions agree that suffering and martyrdom have a place in the tradition. But what they bespeak is the victory of what these people stood for that will outlast the oppression. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all affirm that a martyr’s death is important. But they don’t stop with the suffering. You should get to the point where you say that there was a victory even in this death. That’s what martyrdom is about.