Women Join Talmud Celebration

As the daf yomi cycle of Talmud learning concludes this week, a Jerusalem study group breaks a barrier

This week, hundreds of thousands of people are expected to gather in various venues around the world for what’s being billed as “the largest celebration of Jewish learning in over 2,000 years.” The biggest American event, in New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium on Aug. 1, is expected to fill most of the arena’s 90,000 seats. The occasion is the siyum hashas, the conclusion of a cycle of Talmud study first proposed by Meir Shapiro, rabbi of Lublin, at the First World Congress of World Agudath Israel—an umbrella organization representing ultra-Orthodox Jewry—in Vienna in 1923. Shapiro’s idea was that Jews around the world could build unity by studying the same page of Talmud at the same time. If a Jew learns one page per day, known as daf yomi, it will take almost seven and a half years to complete all 2,711 pages of the Babylonian Talmud. This week’s siyum hashas marks the conclusion of the 12th cycle of daf yomi study since 1923.

Historically, one group of Jews has often been limited in access to this text: women. The ultra-Orthodox world does not, for the most part, approve of women studying Talmud; as one rabbi representative of this view, or hashkafa, explains, such scholarship is “not congruent with the woman’s role” in Judaism. But other ultra-Orthodox, as well as Modern Orthodox and non-Orthodox, communities are making it possible for women to become increasingly involved in daf yomi study.

While tens of thousands pack MetLife Stadium this week, the changing place of women in Talmud study will be apparent at a much smaller siyum hashas thousands of miles away: At Matan, an institute for women’s Torah study in Jerusalem, women will be the ones leading and participating in the gathering.

Matan was founded in 1988, and its raison d’etre is to give women skills and access to Jewish texts, with the goal of creating “the next link in the chain of Jewish history—Jewish women’s Torah leadership.” Matan does not have a specific affiliation, but many of its students identify with modern or centrist Orthodoxy. There are currently 3,000 women in full- and part-time programs at its seven branches around Israel, as well as 3,200 mother-daughter pairs who have participated in its North American bat mitzvah learning program. Matan has hosted a three-year advanced program in Talmud study since 1999; at the beginning of the last seven-and-a-half-year daf yomi cycle, Matan began its own daf yomi group—led by students from its Talmud program.

This week will mark the conclusion of the Matan group’s first daf yomi cycle. According to the director of development at Matan, Chaya Bina-Katz, about a hundred people are expected to attend Matan’s Aug. 2 siyum hashas, which will include a class, speeches, and a meal with students, teachers, families, rabbis, and community leaders.

Yardena Cope-Yossef, the initiator and leader of Matan’s daf yomi group, says that for her, studying Talmud is like having a “wonderful deep ocean to dive into and be inside, not in the sense that one will drown but the opposite feeling: that of being in the depths, and a part of something greater than yourself in the learning process.”

Cope-Yossef has been studying Talmud, which she calls “the most fundamental body of learning of the Jewish people,” since her high-school days at the Ida Crown Jewish Academy in Chicago in the early 1980s. She asked one of the rabbis, a Holocaust survivor named Rabbi Juzint, to sit and learn with her at Ida Crown, where Talmud was not yet taught to girls. She was surprised that he readily agreed, though actual learning was just a few minutes during breakfast break. When she moved to Israel, she began more serious study, inviting a rabbi to teach a private class along with the women with whom she shared an apartment. She went on to study at Matan, and at Hebrew University, at a more advanced level.

For Cope-Yossef, the existence of a women’s daf yomi group at Matan represents “the opportunity to be there, not to fight for what should be a rightful place.” She added that there may be “frustration” or “surprise,” in what one finds on any page of the Talmud but it is satisfying to be “part of something greater than yourself—part of an endeavor of Jewish people around the world and one that spans Jewish history.”

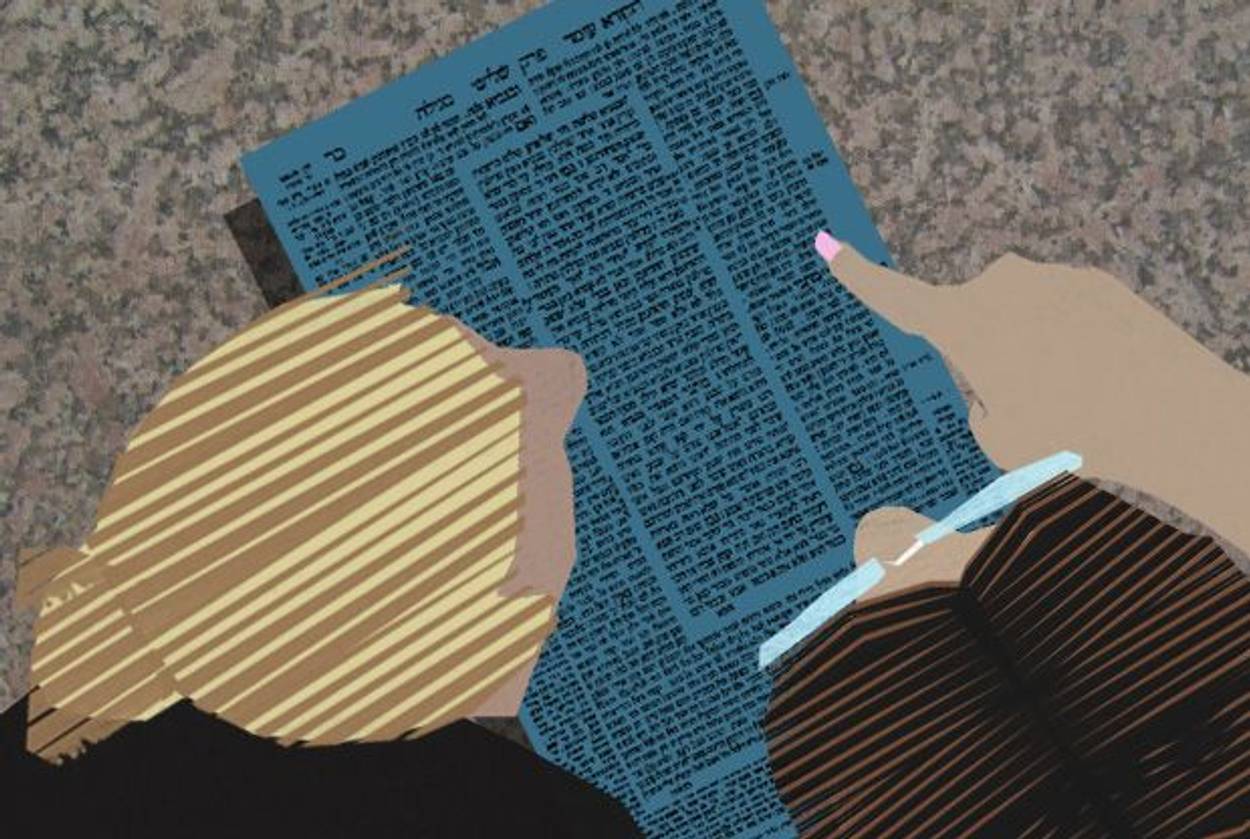

The image of women studying Talmud is still foreign to many ultra-Orthodox men. Debra Appelbaum, one of the members of the Matan group, said in an email that while traveling “a number of us had experiences, whether on the plane or on the New York subway, of men ‘regular’ to daf yomi either doing a second glance or asking to borrow our Gemara—usually, more of the former,” when they saw the women learning the text.

There are women all over the globe who study the daily page either by themselves or with a partner. Nechama Horwitz studied with her father when she was growing up and had female Talmud teachers at both the Stern Hebrew High School in Philadelphia and the Drisha High School Summer Program in New York; she has been learning daf yomi since her seminary days at Midreshet Lindenbaum. “Daf yomi has been a source of continuity during a period of my life in which I’ve gone through some important changes and growth, including finishing my B.A., M.A., making aliyah, and getting married,” she wrote in an email.

But the idea of a group of women teachers and students learning the entire Talmud is still unusual. The women in Matan’s daf yomi group are not interested in making a statement about female abilities, or pulling a stunt; they’re interested in learning the text, studying Torah lishma, for its own sake. Still, Matan chancellor Malka Bina noted that the siyum hashas has special meaning for the women involved: “This is a historic day for Jewish women’s scholarship,” said Bina. “Women have once again proven that they are capable of the same learning qualities as men.”

Elizabeth Shanks Alexander, a professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia and author of a forthcoming book about gender and mitzvot, finds the Matan group’s commitment “personally intriguing.” Alexander studies Talmud every week with the spiritual head of the Yeshiva of Virginia in Richmond and says she admires the “patience with patriarchy” that women who “inhabit the piety of the Talmud” in traditional communities have.

Jacob J. Schacter, a Modern Orthodox rabbi and professor of Jewish history and Jewish thought at the Center for the Jewish Future at Yeshiva University, commended the Matan group’s efforts: “One of the blessings of our generation is the growing number of opportunities granted women for serious Torah study,” he wrote in an email. “Completing daf yomi is an extraordinary achievement for women, as well as for men.” At Yeshiva University there is a graduate program in Advanced Talmudic Studies at Stern College for Women, a two-year program for women to study Talmud; the first woman to receive a doctorate in Talmud from Y.U. completed her degree last summer. Women have been receiving doctorates in Talmud from the liberal seminaries, as well as universities in America and in Israel, since 1982, when Judith Hauptman, currently chair of the Department of Talmud and Rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary, became the first woman to earn the degree.

The Modern Orthodox world is expanding the places where women study and teach Talmud, in single-sex and co-ed classes and forums. At an Aug. 6 Modern Orthodox siyum hashas event in New York, both men and women will speak, including Matan’s Cope-Yossef; Matan is one of the event’s co-sponsors.

There are even some in the ultra-Orthodox world who would agree that women should study Talmud. The late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, wrote that women should be supported and encouraged to study Talmud, both on the strength of the example of the historical figure of the learned Bruria—the daughter of Rabbi Hanina ben Teradion and wife of Rabbi Meir, cited as an authority in passages of the Talmud itself—and because it is important for women as well as men to understand the basis of Jewish law and the oral Torah. Aaron Herman, the rabbi who serves as principal of the Tzohar Seminary for Chassidus and the Arts in Pittsburgh, and a follower of the late Rebbe, teaches the young women at his school “some Gemara,” the more complicated part of the Talmud, which expands and discusses the ideas found in the Mishna. “I would have felt remiss had I not done so,” he noted. “It would be my desire to teach even more Gemara if time allowed.”

Gail Labovitz, a rabbi who teaches in the Talmud department at the Conservative movement’s American Jewish University in Los Angeles, is also concerned about the role of Jewish women. “The opening of serious, strenuous Torah study to women is, in my opinion, one of the most significant social developments in the Jewish world in the last 50 or so years,” she said. Labovitz decided to study daf yomi for the first time after seeing a colleague give a siyum hashas during the previous cycle of learning; she encourages other women to follow suit. “Women have been shut out of the process by which Jewish texts and learning and practices were shaped for most of Jewish history,” she said. “As they become ever more versed in our textual tradition, however, it will be harder and harder to keep those doors shut.”

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.