Where the Wild Things Aren’t

An author realized all the best kids’ books were about Gentiles. So she started writing.

I’m a Jewish author, and when I was writing for grown-ups, my religious background and my writing blended together nicely. I wrote radio commentaries about Passover and edited a book on interfaith marriage. It felt natural. Then I began to write for children, and somehow, my Jewish identity—and my own search for religious meaning and a place in that community—fled my work entirely.

At first I didn’t notice that anything was missing. I just went on, scribbling about towheaded children and magical critters, until, one day, a tiny Santa Claus popped up in my very own picture book, Inside the Slidy Diner. The book was already finished, printed and bound, the day I looked down and saw him peeking out at me from a glossy page. He was a minor detail, but still he was there, snowy beard and all.

Of course I was bothered. I don’t, as a rule, keep books with Christian elements in my own home, and yet here, in my book, was Father Christmas himself. Still, I couldn’t fault the artist, since there was nothing in the text to indicate what I had assumed people would know—that the book was Jewish because it was written by a Jewish author.

Which got me wondering why. Why wasn’t I writing Jewish books for kids? Or at least working Jewish characters and themes quietly into my secular writing? Would it kill one of my characters to light candles on Shabbat? I was upset by this suddenly obvious absence, and mulled it over for weeks. Finally, I reached two conclusions.

First, that most of the books I had loved as a child—from Eloise to Mister Dog—weren’t Jewish. So in attempting to write within the tradition I admired, I had inadvertently begun writing gentile characters. This didn’t seem so bad to me. Whenever I consume too much Eastern European poetry, I end up writing about turnips. I’m a chameleon as a writer, and that’s a good thing. It means I reinvent myself periodically.

But my second conclusion was more troubling. As a Jewish children’s author I simply don’t have many really fabulous models. There are too few Jewish children’s authors writing artful, fanciful, humorous books that also happen to be thematically Jewish. I don’t like most contemporary Jewish kids’ books and so I don’t write them. That’s a problem.

Most books for young Jewish readers are instructional. They have titles like, Purim Goodies or It’s Israel’s Birthday! and they’re intended to educate kids about specific customs, traditions, events, and places.

Which is fine, if you’re looking for instruction (though most kids aren’t, if you ask me). But I’m not the kind of writer who sets out to indoctrinate. I seek to entertain and maybe inspire. I hope that kids will learn and grow when they read my books, but I don’t usually have a specific lesson in mind, because I think the most effective way to teach ideas or values is through an adventure or journey, and most of all through characters that exist for their own sakes.

Don’t get me wrong—I don’t mean to suggest that our kids don’t have anything worth reading. I love The Runaway Latkes, and it’s a good indicator that we’re moving in the right directions. We have wonderful Golem retellings and collections of incredible bible stories. But those books are outnumbered by edutainment that relies on old models. Illustrations that could have been painted for a ketubah. Stories set in shtetls. We need more kinds of books for our kids, books that are fresh and funny, that speak our kids’ language, whatever that is, or becomes.

I want to believe things are improving, but if they are, it isn’t fast enough. And while there do seem to be strides in Young Adult literature, the shift doesn’t seem to be having much of an effect on books for our youngest, most easily affected readers. If you think I’m wrong, try doing a Google search for Jewish picture books and see what pops up.

I can imagine the Jewish books I want for my kids. A crazy range of things—from updated dybbuks, mystical legends and weird Talmudic lessons, to honest depictions of intermarried families and the ongoing diaspora most of us experience everyday. I can envision sweet, silly characters and ridiculous situations—a rabbinic Cat in the Hat. A crazy time-traveling sukkah. Books as wild and wonderful as anything the secular market offers. I can imagine them. Now I have to write them.

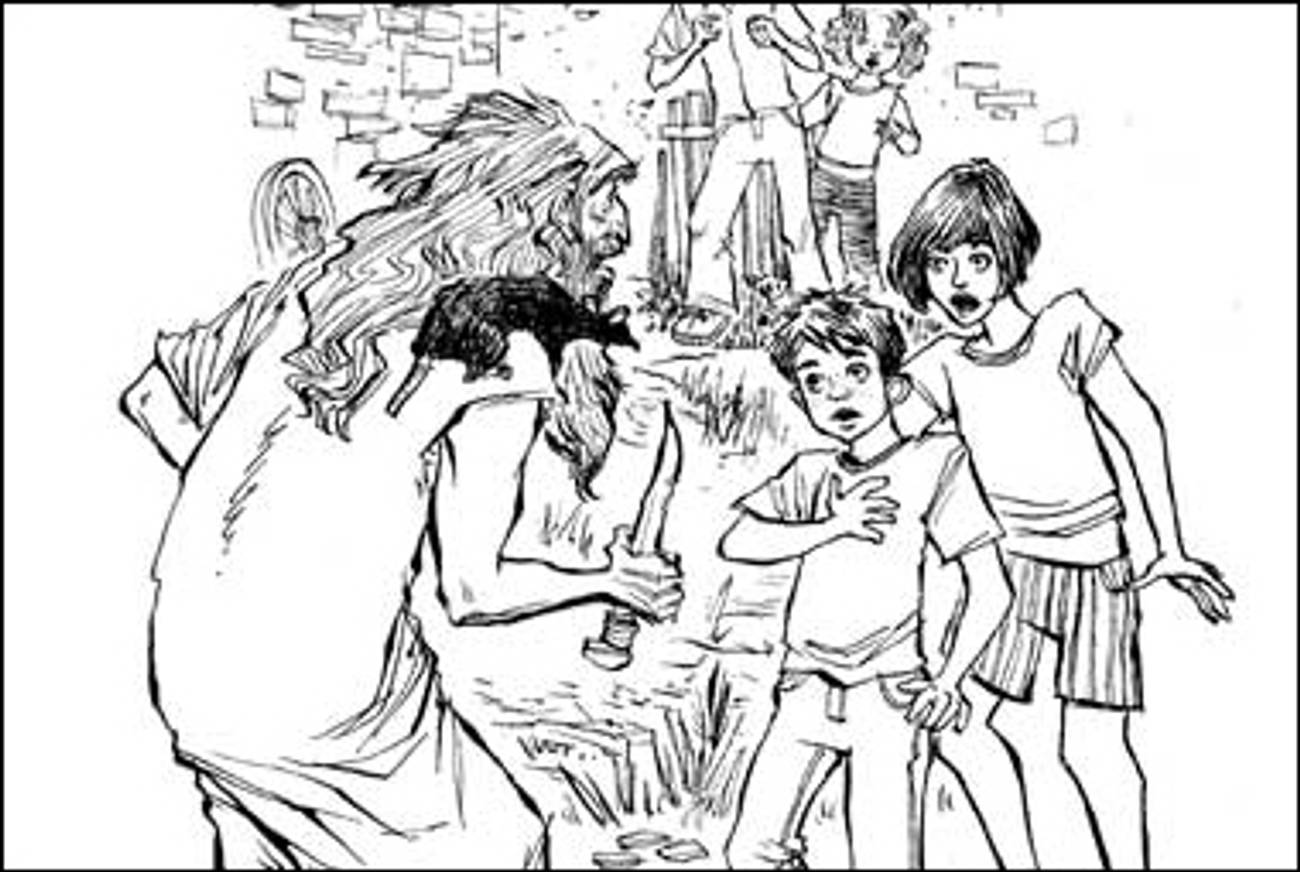

Of course, this realization came too late for Slidy Diner, but I did manage one small change in the book I was finishing at the time, Any Which Wall. Just as the book was going to print, I convinced my editor to change the name of a central family, from Simpson to Levy. It was a small first step, but to me it felt like something—a symbolic shift, a promise I was making—to try to write for the self I was as a kid—a little girl in love with magic, humor, and the big wide world around me, but also a little girl who happened to be Jewish.

I was so excited to see the word Levy in the page proofs for the new book, I began work on a picture book called Baxter the Kosher Pig, about how insecurity and misunderstanding once kept a little pig from finding his community. The book came out in a rush, and thrilled with the results, I quickly sent it off to an esteemed publisher of Jewish children’s books.

Almost overnight I received a rejection, a kind note explaining that while the press liked my voice, and the story, and while they thought Baxter was cute and funny, the idea of a pig wanting to be kosher was too risky. They said they could not afford to “alienate their readers.” Could Baxter be something besides a pig, they wondered.

No, he couldn’t. That was the point of the story. I was crushed.

This was a lesson in exactly how the status quo stays the status quo. In how Jewish institutions define (and bore) the less traditional members of the community. The institutional world is a nervous one, mindful, always, of upsetting its most affiliated members.

So I learned from the experience, and went out in search of a risk-taking Jewish editor. To my great good fortune, I found her—a wonderful editor at a secular press. She is someone who believes—as I do—that there are smart, absurd, iconoclastic, thinking, reading, Jewish parents in the world. People bored with latkes and tree planting, people convinced that stories are exactly the place where kosher pigs should exist.

Now we’ll leave it to the free market to determine what Jewish parents really want. We’ll trust you to read deeply. To recognize Jewish values and identities, even without the hechsher.

Laurel Snyder is the author of several books. Her most recent, Any Which Wall, is out now from Random House.

Originally published on February 18, 2009.