Drawing on Experience

In fashioning his sculptures, Jacques Lipchitz drew inspiration from his sketches—and his past

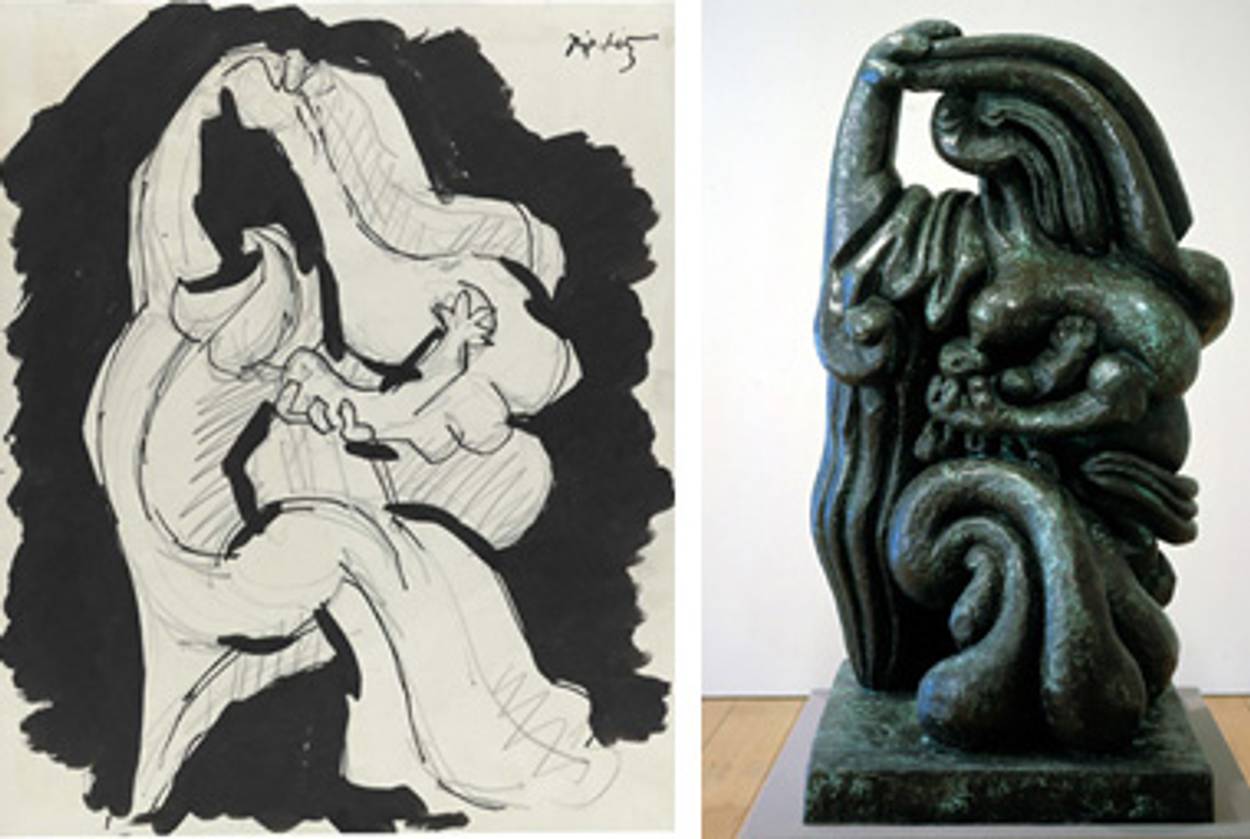

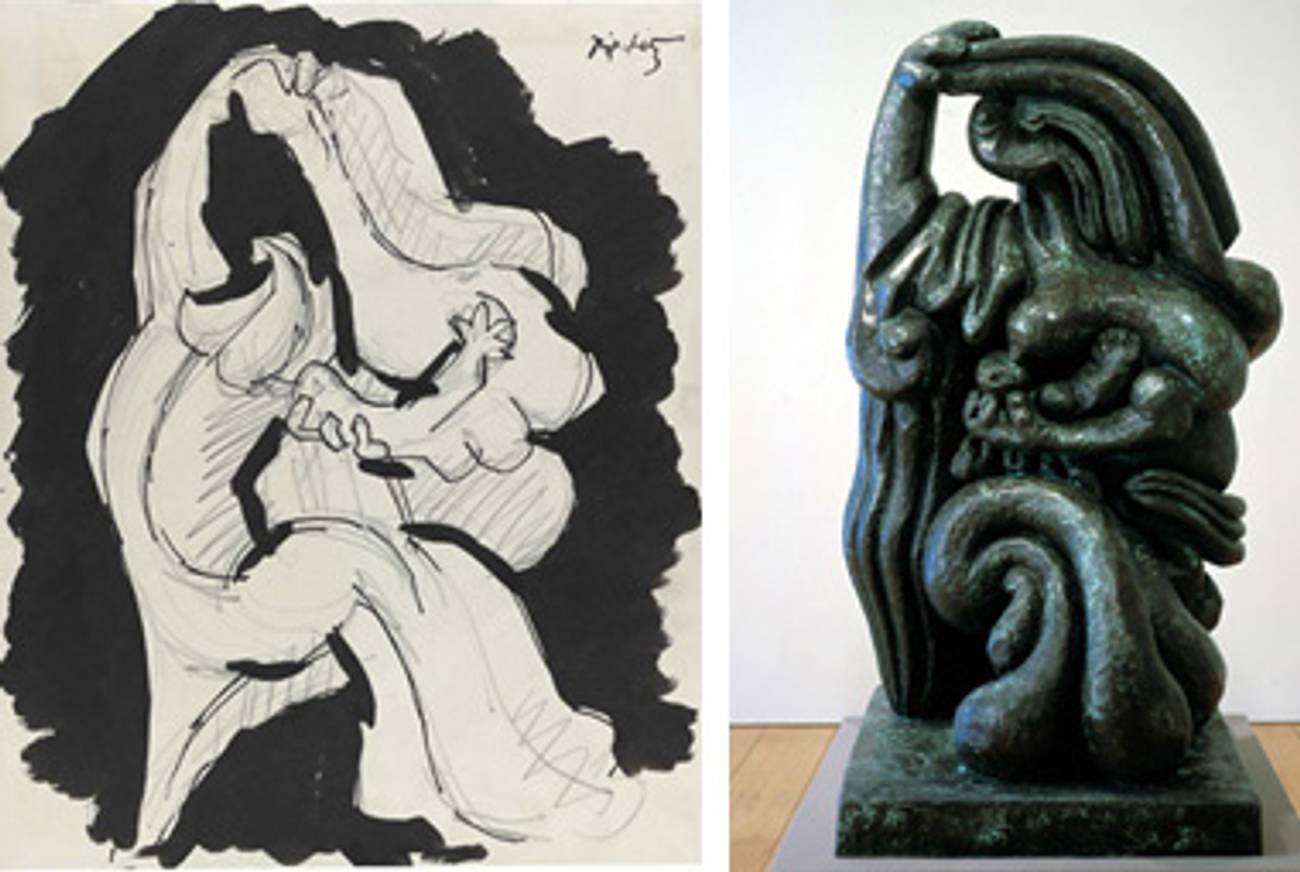

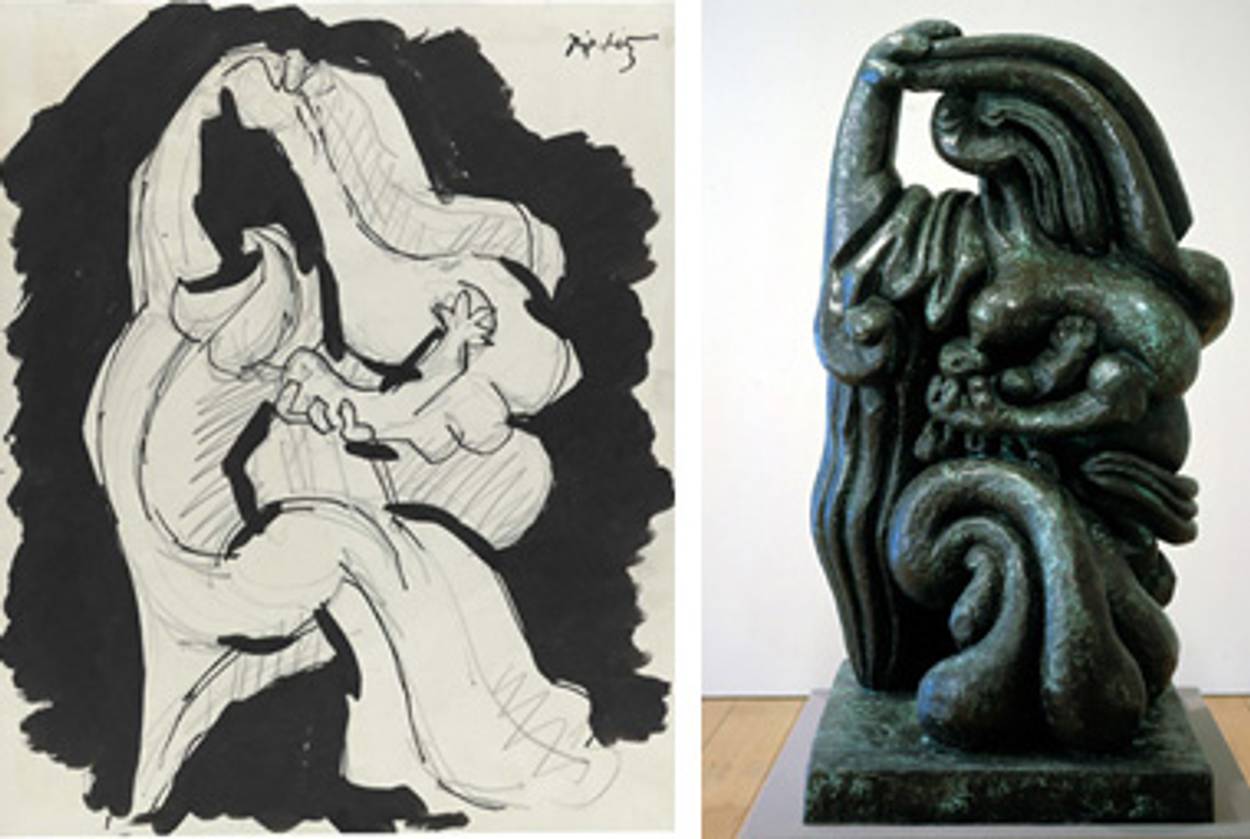

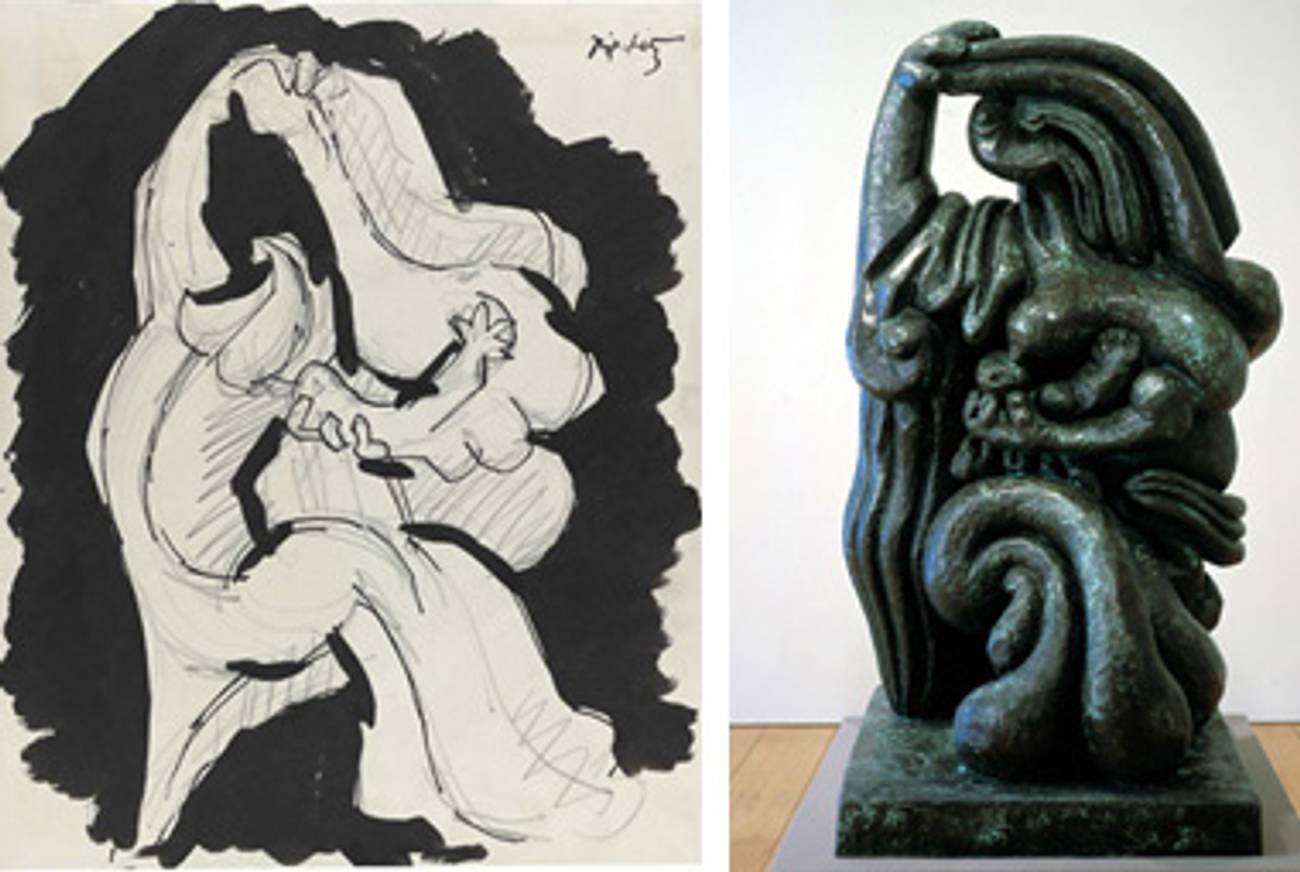

Jacques Lipchitz is best known as a cubist sculptor, but his engagement with cubism was hardly straightforward. And while he asserted that the drawings in which he worked through his sculptural variations were never made “as independent works of art,” Lipchitz demonstrated tremendous skill as a draftsman and a lifelong fascination with the medium. Master Drawings: The Anatomy of a Sculptor, at London’s Ben Uri Gallery (the Jewish art museum founded by Lipchitz’s friend and fellow Litvak Lazar Berson in 1915), traces the development of his central ideas in 152 works on paper from an anonymous private American collection. In the process, this first British survey of Lipchitz’s work in over 20 years, on view through July 26, also offers fresh insight into the more famous, three-dimensional creations.

As Lipchitz scholar Catherine Putz notes in the introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue, the Lithuanian émigré, born in 1891, spent his formative years among a circle of École de Paris artists whose “fascination with natural geometries had its intangible mystical aspect as well as its precise analytical dimension.” On the one hand, she argues, Lipchitz “was thinking spatially and from multiple viewpoints,” but she reminds viewers that he industriously studied anatomy in the city’s academies upon his arrival in 1909 and later pronounced that “even in my most abstract phase, I was always drawing after nature.” Beyond this duality in approach, his style evolved markedly over the course of a prolific career. While reductive, angular forms made between 1913 and 1924 established Lipchitz’s enduring reputation as perhaps the first and most significant cubist sculptor, he gradually moved away from this formal language, embracing a more personal, expressionistic idiom.

Much as Lipchitz’s sensibility shaped his dynamic oeuvre, the circumstances of his life shaped his sensibilities. The eldest of six children born to well-to-do Jewish parents, Lipchitz moved to Paris at the age of 18, quickly joining an avant-garde that included Picasso, Juan Gris, Brancusi, Modigliani, and Max Jacob. The 1940 Nazi occupation forced him to flee to Toulouse and, the following year, to seek asylum in the United States, where he found success in the New York art world. Even before this tumult, pure cubist experiments gave way to complex “transparents”—pierced forms accentuating negative space against sculptural mass—and increasingly fluid, organic figuration. However, World War II and the direct threat it posed for Lipchitz did precipitate forays into more somber, emotionally charged imagery, while his 1948 marriage to Yulla Halberstadt and the birth of their daughter Loyla sparked renewed interest in his religious heritage and explorations of the precarious, but ultimately triumphant, human spirit. He became particularly preoccupied with biblical and mythological subjects, infusing his figures with dramatic depth that he attributed, in part, to “the disruption of my entire life,” and celebrating love as “a kind of hope.”

All this is documented in the drawings, which elucidate what Putz calls Lipchitz’s “protracted meditation on one idea or motif over many years,” as well as his determination to effectively transplant his deeply emotional musings into the three-dimensional, often monumental, realm. Perhaps as significantly, this body of work, shaped by Lipchitz’s personal experiences, offers what museum co-chairman David Glasser calls “intelligent and complex investigations into some of the most challenging pivotal moments of twentieth century European experience.”

Jeannie Rosenfeld, a Tablet Magazine contributing editor, writes about fine and decorative art.

Jeannie Rosenfeld, a Tablet Magazine contributing editor, writes about fine and decorative art.