Making It

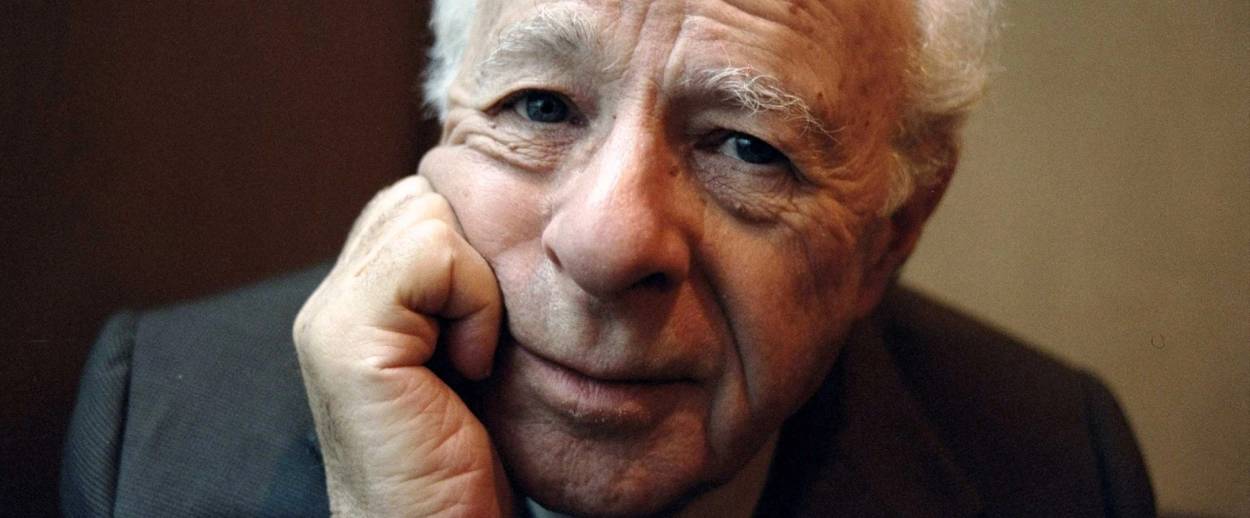

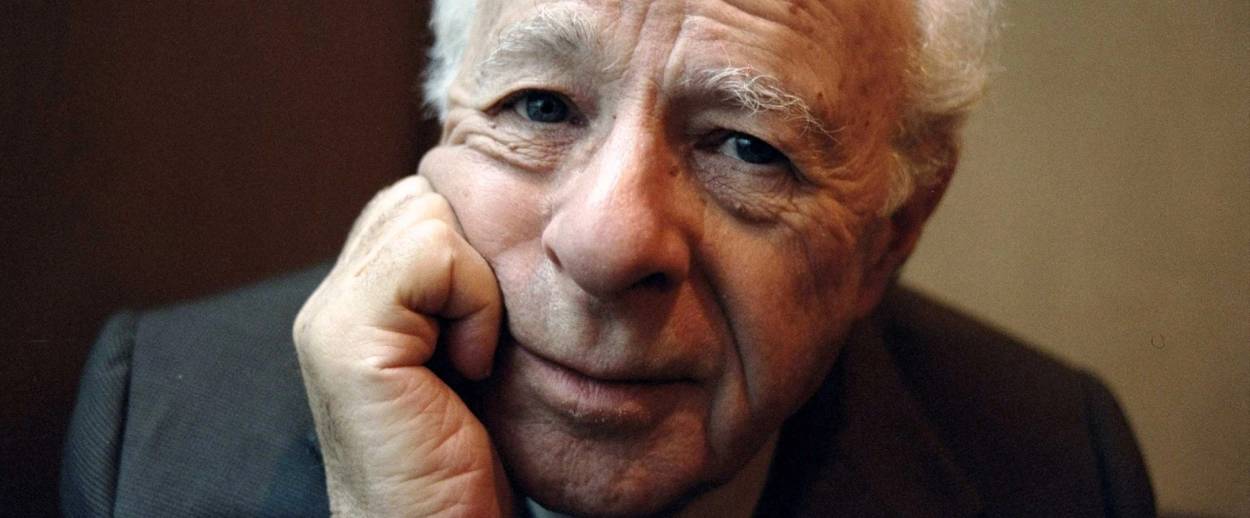

As Norman Podhoretz turns 89 today, he looks back on the long journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan

The most famous first line in 20th-century American literature set in Kings County, New York, must be incomprehensible to many current residents of that highly literary territory. “One of the longest journeys in the world,” writes Norman Podhoretz in the opening of his 1967 autobiography, Making It, “is the journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan.”

Podhoretz was of course speaking figuratively, referring to cultural and class differences separating the two boroughs that were infinitely wider than the East River. Today’s Brooklyn is different—apartment hunters are likely to find it less expensive to live off Park Avenue than in Williamsburg, Cobble Hill, or Fort Greene, where rents have soared due to the constant influx of tech-savvy millennials.

But back in the day, the price you paid to get from a working-class Jewish enclave in Brownsville to Columbia University and then the literary salons of the Upper West Side was constant re-invention, repeatedly shuffling off old selves and girding on new ones. That journey, as well as Podhoretz’s political transformations, from liberal to leftist to conservative, maps the last six decades of American society and culture and the Jewish community, and where and how they intersect. Today, he turns 89.

We’ve met several times over the last few years, first at lunch close to his home on the Upper East Side. “Here’s where Madonna lives,” he told me on the sidewalk, pointing to a large fortress-like structure, as if to note how the neighborhood of white-shoe lawyers and Wall Street financiers had morphed into something from Page Six.

I wanted to speak with Podhoretz for the same reason I’ve read and reread his work over the years—especially, in addition to Making It, Why We Were in Vietnam, The Bloody Crossroads: Where Literature and Politics Meet, and his two other autobiographies, Breaking Ranks and Ex-Friends. He seemed to me to hold the keys to the vault that contains the blueprint for how we as Americans, how I as an individual, got here, and where we’re going.

He’s taken up the struggle between liberal and conservative politics that re-generates our public life, and tells the truth about the drives of the ethnic New York through which much of the country passed before fanning out to fill and build America. Maybe most importantly to me, it’s because his political and cultural sensibility is shaped by his experience of literature. He takes texts, from the Bible to the modern novel, seriously.

It’s easy to forget that the writer perhaps best known for his essay “My Negro Problem and Ours” and one of the intellectual fathers of neoconservatism, especially in foreign policy, studied with Lionel Trilling and F.R. Leavis, two of the greatest literary critics of the 20th century. He wanted to be a poet. Making It is a song of self filtered through a Brooklyn idiom: Here’s who I am—take it or leave it.

We spoke most recently on the phone after I visited him last year in his apartment on the Upper East Side shortly after the New York Review Books re-issued Making It in their classics imprint.

He greeted me at the door with his wife, the writer Midge Decter, and daughter Ruthie Blum, an Israeli-American journalist. Their other children are Naomi Decter, the late Rachel Abrams, and son, John, editor of Commentary magazine. Norman edited the magazine from 1960-1995, leading it through at least two political and cultural transformations, first taking it from liberal to leftist and then swinging it back the other way to conservatism.

Podhoretz told me he just re-read Making It recently and enjoyed it. The circumstances of the book’s re-issue were gratifying—and surprising.

“The opposition to Making It when it first came out was more or less led by people associated with the New York Review,” said Podhoretz. “Jason Epstein [NYRB founding editor] said don’t publish it. Bob Silvers [the late editor of the NYRB] and that whole crowd were violently against the book. Most of them thought it was terrible. So to have gotten this imprimatur from the New York Review—for them to reissue it and call it a classic—was not something I ever expected to live to see.”

At the time it was unusual for younger writers—Podhoretz was 37 when it came out—to publish their memoirs. They simply hadn’t done enough to merit the attention. But it’s still difficult to understand why the reaction was so violent. After all, the book is essentially modeled after a popular literary genre, the novel of education, the bildungsroman—in which Podhoretz himself plays the role of Huck Finn, navigating the waters of New York intellectual culture in the 1950s and ’60s and the people, friends, and hucksters, he meets along the way. In Nietzschean terms, it’s the story of how he became who he is.

Yet the paradox of that effort is that, at the time, the most disruptively Nietzschean gesture, the transvaluation of values, was to praise bourgeois mores. “The reigning ethos was the counterculture,” said Podhoretz. “There was a violent ideological opposition to anything in middle-class culture. The counterculture was reigning supreme.” To run counter to the counterculture and write in praise of ambition and success, said Podhoretz, “was the ultimate intellectual heresy of that period.”

What seems to have most unnerved the intellectual classes was the author’s expression of love for America, not just its possibilities, but also the character of the country and its citizens. Podhoretz’s affection for America and its people blossomed during the two years he spent in the army, from 1953-1955.

“I hadn’t really known that much about America, Americans,” said Podhoretz. “I’d hardly ever been anywhere. I was a counselor in a camp in Wisconsin. But it was a Jewish camp and I didn’t really get to know people out there. Interestingly enough, Henry Kissinger told me he had exactly the same experience when he got in the army. He discovered Americans, and they are wonderful.”

One of the book’s pivotal scenes takes place in a bar in Frankfurt, when Podhoretz is harangued by a former Waffen SS soldier. After Podhoretz tells the German he’s Jewish, the Nazi throws his arms around him and says that all the stories about the Jews were British propaganda.

Podhoretz storms out of the bar accompanied by an army buddy, who, not understanding German, wanted to know what happened. Podhoretz discovered that his friend, a recruit from Mississippi, did not know much about the Holocaust or that Podhoretz was Jewish. “Oddly enough I was rarely recognized as Jewish,” Podhoretz told me. “The name did not sound Jewish to most people.”

Podhoretz documented in Making It how his friend from the Deep South responded: “Let’s go back in there and kill the dirty kraut bastard.” Years later, Podhoretz vividly recalled the incident. “He broke a beer bottle and went after this German,” he told me. “It was no fooling around.”

At the time, the unschooled American farm boy was a stock character worthy only of disdain. So what if the teenagers from around America who manned the Fulda Gap to protect Western Europe from the Red Army for decades afforded Sartre and his pals the peace they filled with philosophy, Pernod, and praise of Stalin? Those kids were a punchline from Paris to the Upper West Side. Podhoretz showed instead that this kind of American was a fundamentally good human being who instinctively does the right thing.

Podhoretz won their admiration in return. “The fact that I was not only a college graduate but had graduate degrees, there was tremendous respect and deference from them. Far from feeling superior to those guys, I felt like they were great, different types from all over the country and they were overwhelmingly interesting, charming, funny. As soldiers they were better than I was—for the most part. I was a good soldier. It was the one thing that Pat Moynihan always esteemed me for when we were friends was that I was once a soldier of the month.”

I asked Podhoretz if he thought this was one reason why lots of people in places like New York don’t understand President Donald Trump or his supporters. That’s part of it, explained Podhoretz. But he doesn’t quite understand why New Yorkers don’t recognize Trump as so clearly one of their own.

“If you’ve known New York real estate people like I have,” he said, “he’s a paradigmatic example. I never met Trump, but I know a lot of people in that business. So I know what it’s like to succeed as a New York real estate-nik.”

I told him that I’d never heard that phrase before—real estate-nik. “Oh yeah, it’s very common actually,” said Podhoretz. “You know people say jokingly Trump is Jewish. He’s not literally, but if you’re a real estate guy in New York, you’re sort of automatically Jewish.”

Why then, do so many Jewish conservatives, including members of the neoconservative movement that Podhoretz led, dislike Trump?

“I think the deepest reason was that that a lot of people on the right, not just neoconservatives, saw him as a new McCarthy test. And they thought that Bill Buckley had made a great mistake in supporting McCarthy, as he later admitted. So Trump was a sort of a moral political test of how you define the limits of conservative respectability. And therefore it was absolutely crucial to take the right stand.

“Now nobody actually said this, as far as I know,” he continued. “But I think if you took an X-ray of what was going on in the heart of most of the Never Trumpers on the right there would be something like that involved. This was a moral test the way McCarthy was a moral test for the right in the ’50s.”

There was also some snobbery, said Podhoretz, “and genuine shock that somebody who knew so little was so full of self-confidence despite his ignorance. They did think he was unfit for office. So, for some people it also has to do with their refusal to accept the legitimacy of the 2016 election. It wasn’t supposed to produce a guy like Trump. Andrew Jackson inspired similar feelings in his day.”

Podhoretz himself describes himself as being initially anti-anti-Trump. “I just couldn’t stand the opposition and I gradually moved from there into being pro-Trump which I still am.”

He describes two Trumps—a conservative Trump and a Twitter Trump. The first is the most conservative president “in his appointments of anyone since Reagan. From a conservative or neoconservative perspective, the appointments of Pompeo and Bolton couldn’t be better.” The Twitter Trump, said Podhoretz, “decided he was going to dance with the girl he came with—which was himself. He wasn’t going to try to change into what they called presidential.”

Podhoretz is another outer-borough New Yorker who enraged an embedded establishment by following his own instincts—and wasn’t always proven right, not right away anyway. While The Art of the Deal may not survive as an American classic, Making It will—but the titles strangely seem to belong on the same shelf.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).