Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

Why Jewish producers kept Jewish women off stage and screen

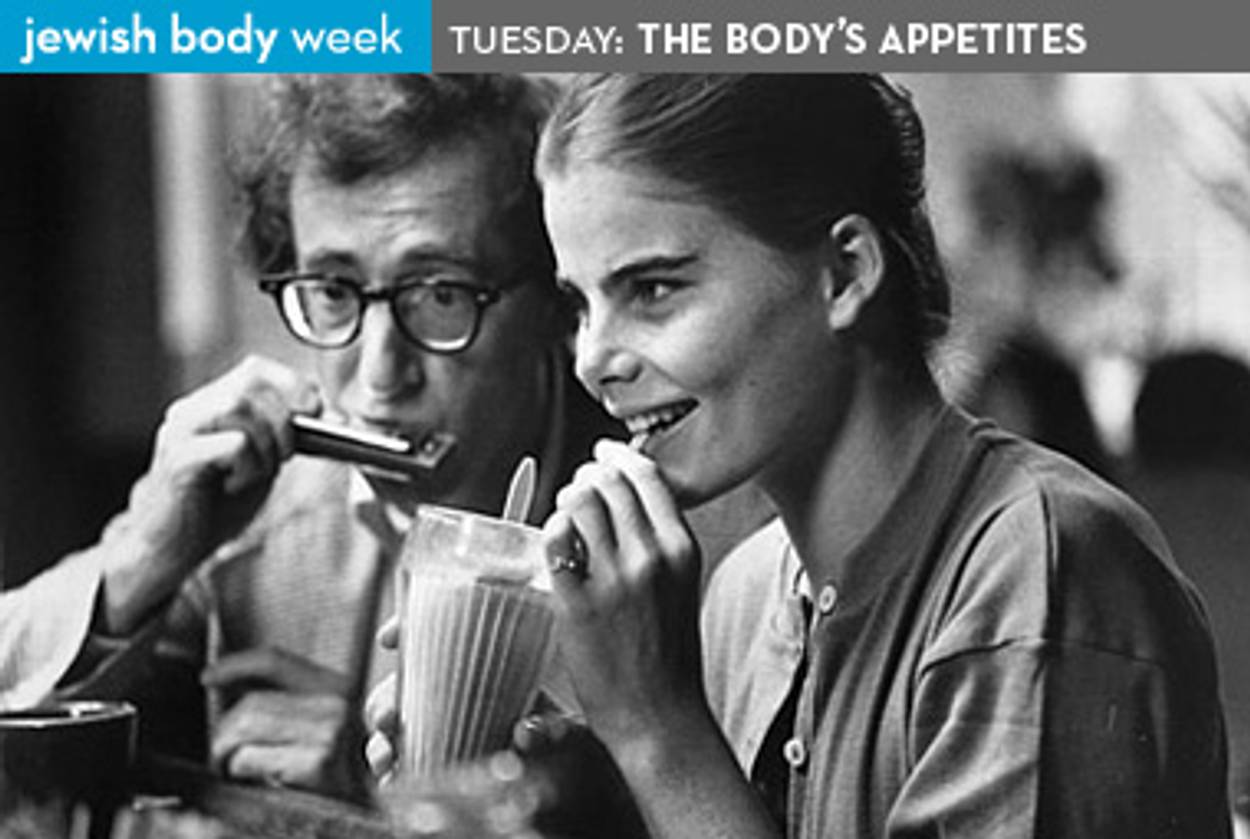

A friend of mine—I’ll call her S.—has much to be proud of. She’s an accomplished actress, a terrific mother, and a loving wife. Yet the one thing she’s best known for doesn’t involve her at all: when she was a teenager, she had a brief but tumultuous affair with Woody Allen, a man many years her senior, a tryst that ended up serving as the raw material for Allen’s Manhattan. When the writer and director recreated the relationship on film, however, he did not choose someone who looked like S.—a Jewish beauty with dark, curly hair—but opted instead for Mariel Hemingway, so much of a stereotypical all-American girl that her blue eyes and blond hair came across even in the black-and-white film.

While S. is too prudent to comment on this switcheroo, one does wonder what may have motivated the transformation: why turn a bright-eyed brunette into a fair-haired ingenue?

This, of course, is not a new question, nor is it limited to S.’s experience. Since the dawn of American entertainment, Jewish women were largely rendered invisible, absent everywhere from burlesque to Hollywood to prime-time television. Instead, they watched as their sons and brothers and husbands became successful producers, directors, and impresarios, powerful men who then chose to populate their works with a parade of sexy, sultry shiksas who looked nothing like their female kin.

Perhaps the first exponents of this tradition were the Minsky Brothers, the influential proprietors of a popular New York City burlesque empire in the first decades of the last century. “If you were a burlesque stripper, you had to be a blonde or a redhead, never a brunette,” Rachel Shteir, author of Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show told me. The brothers, she added, had a readymade explanation for their proclivities: Jewish women, they argued, were simply too pure to lust after. “They would say, ‘we’re not stealing your mothers and sisters and aunts and putting them on stage and taking away their honor,’” Shteir said. “They would say that they were only putting the shiksas on stage. As heinous as it is, that was their reasoning.”

And yet the Minskys’ aesthetic exclusions may have played a part in helping their patrons, many of whom were first-generation American Jewish men, adapt to their new society by becoming accustomed to its ideals of beauty, whether real or imagined. “I think one of the functions of striptease in that time period,” Shteir said, “was that it became a social space where men could be Americanized by watching these women who were nothing like their sisters and mothers. The Jewish women, however, would stay at home and in the community. They were not exposed.”

For the Minskys, American beauty was exclusively yellow- or red-haired, cute and perky, never dark, never familiar. And the same ideal of beauty they helped cement found its way into the mainstream of American culture through that much more influential maker of popular entertainment, Hollywood. The Minskys’ contemporaries who went out west, men like Adolph Zukor and Louis B. Mayer, banished Jews in general, men and women alike, from their productions, in part to avoid accusations that they were using film to subvert America’s traditional values.

“As Hollywood Jews were being assailed by know-nothings for conspiring against traditional American values and the power structure that maintained them, they were desperately embracing those values and working to enter the power structure,” wrote the historian Neal Gabler in An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.

A few decades later, as the zeitgeist shifted and Jewish producers, directors, and writers found themselves increasingly comfortable with allowing Jewish characters into the spotlight—Allen himself being perhaps the most obvious example—that light shone exclusively for Jewish men. They, usually jittery and neurotic and smart, were allowed to roam the savannas of the movie screen, usually in search of the same idyll the Minskys knew so well, the blonde American vixen.

Which, of course, left the few Jewish actresses who managed to achieve a modicum of success flummoxed. Take Jennifer Grey: the actress, best known for her role as the romantic lead in Dirty Dancing, eventually decided to have a nose job and alter what was, perhaps, her most prominent facial—and, stereotypically speaking, ethnic—feature. “The thing is,” she told a newspaper reporter who questioned her about her rhinoplasty, “Hollywood is run by Jewish men. We all know the Jewish syndrome in high school. The Jewish boys don’t like the Jewish girls.… They really want the goddesses and Michelle Pfeiffers.”

The same Jewish boys very often ran not only Hollywood but the large television networks as well. In his pioneering account of Jewish representations on TV, The Jews of Prime Time, David Zurawik, the Baltimore Sun’s television critic, noted that long after Jewish television executives became relatively comfortable allowing male characters named Fisher and Steinberg and Seinfeld to entertain the heartland, they still required their creations to lust after women who were decidedly non-Jewish.

In the last two decades alone, a slew of shows centered around that very theme found its way to prime time, some successfully and others less so. There was Anything But Love, about a neurotic Jewish writer pining after a gorgeous and free-spirited researcher; Flying Blind, about a neurotic Jewish business executive pining after a gorgeous and free-spirited libertine; Chicken Soup, about a neurotic Jewish pajama salesman pining after a gorgeous and free-spirited activist; Mad About You, about a neurotic Jewish filmmaker pining after a gorgeous and spirited public relations executive; the list goes on.

Each of these series, Zurawik wrote, were designed around the idea of transformation, or, more accurately, around the power the non-Jewish woman—a goddess, after all—had to extricate her Jewish lover from his suffocating, crass, and unhealthy environment and introduce him to her clean, well-lit world. It’s no wonder, then, that a survey conducted a decade ago by the Morning Star Commission, a group of writers, scholars, actors, and journalists funded by Hadassah Southern California, found that Jewish women, on the rare occasions they did appear on screen, were mostly perceived as “pushy, controlling, selfish, unattractive, materialistic, high maintenance, shallow and domineering.”

Will a new generation of producers, many of whom are Jewish women, change any of these stereotypes? Lynn Roth, a former executive at 20th Century Fox, is not optimistic. “It’s odd,” she told Zurawik, “because there are so many [Jewish] women involved in the decision making process now and they’re just continuing the stereotype. I don’t think they’re making any difference.”

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.